How to correctly interpret the continuous shooting speed information

People like to show off with technical specifications, but they can also be misleading. When it comes to cameras, there is hardly a value with more footnotes in small print than the continuous shooting speed. This is because the actual speed depends on many factors.

The Canon EOS 1D X III is a sports and action camera for professionals. It manages 16 images per second - an exceptionally good value. But wait a minute! Aren't there quite affordable devices that can take 20 pictures per second? Can't even mobile phones quickly save 100 continuous shots if you hold the shutter button down for a moment?

Is a sports photographer's camera slower than his mobile? Wouldn't that be totally ridiculous?

It's a bit like taking a maths test. Simply being fast is not particularly difficult - and not particularly advantageous either. The aim is to be fast and good. Whether the picture turns out well depends on the conditions under which the continuous shooting speed can be achieved. And that's where the differences lie.

Mechanical versus electronic shutter

A classic camera has a mechanical shutter. This dates back to the days of analogue photography, when the film negative always had to be protected from light - except for the brief moment when the picture was taken. In principle, this is no longer necessary today. The sensor, which has replaced the film, can be constantly exposed to light. The exposure time can be controlled electronically. This means that the camera records the data from the sensor that it has measured in the specified exposure time and then resets all the sensor values. This process is called an electronic shutter.

With a mechanical shutter, physical parts have to be moved. You therefore hear a quiet noise with every shot. With an electronic shutter, nothing moves. This is why higher speeds are possible with an electronic shutter.

A mobile phone does not have a mechanical shutter. Even simpler digicams sometimes lack one. But why does a sports camera of all things still have a mechanical shutter if it slows the camera down?

One reason is the rolling shutter effect. Objects that move very quickly are distorted. This looks particularly blatant with propellers. The rolling shutter effect is caused by the fact that the different areas of the sensor are not exposed at exactly the same time. Although this is also the case with the mechanical shutter, it is much less pronounced.

A mechanical shutter can cycle through the entire sensor within 1/8000 of a second. As light only reaches the sensor within this cycle, it is ensured that the individual pixels are exposed within this 1/8000 of a second. This is not the case with the electronic shutter. The pixels can be exposed just as quickly, but only with a relatively long time delay. The sensor is read out line by line and then reset. With the current state of technology, this takes too long to prevent a rolling shutter effect.

Another problem occurs with certain artificial light sources, such as neon tubes. These flicker at the frequency of the AC mains, i.e. 50 times per second. You hardly notice this with the naked eye, but with fast shutter speeds this means that not all parts of the image are evenly exposed.

Many cameras have an anti-flicker function that prevents this. It does nothing other than expose the image until the effect is no longer visible. However, fast shutter speeds are desirable for fast continuous shooting. After all, the aim is to capture fast movements.

Autofocus

In current top cameras, the autofocus can keep up with a high continuous shooting speed. However, this is usually not the case, and this can lead to massive losses.

The first question is: Is the specified speed achieved with tracking autofocus or is it only focused once at the beginning of the series? In the second case, it can easily happen that the majority of the images are blurred.

If the manufacturer states that the values apply to tracking autofocus, that's a good thing. But even then, the autofocus can act as a brake. This is because its speed varies greatly depending on the subject, lighting situation and settings. The lens also plays a role, as the focus motor is not equally fast with all lenses.

Many cameras can be set so that the continuous images rattle through, even if the autofocus could not focus in time. On my Nikon camera, this is even set at the factory and is called "shutter priority". This doesn't slow down the autofocus, but it does result in a lot of blurred images. This only makes sense if the time interval is more important than the sharpness, for example in a stop-motion video.

Saving speed

The vast majority of cameras cannot maintain their maximum continuous shooting speed for long. After a few seconds, it drops quite drastically. Namely when the buffer memory is full.

Saving a photo takes place in two steps: First, it is stored in the buffer memory and written from there to the memory card. As soon as the image is on the card, it can be deleted from the buffer memory. Normally, the write speed of the memory card is significantly slower than that of the buffer memory. As a result, the buffer memory fills up more and more. After around ten to one hundred images - depending on the camera - it is full.

The buffer memory fills up less quickly if you use the JPEG format, as smaller amounts of data are generated here than with RAW.

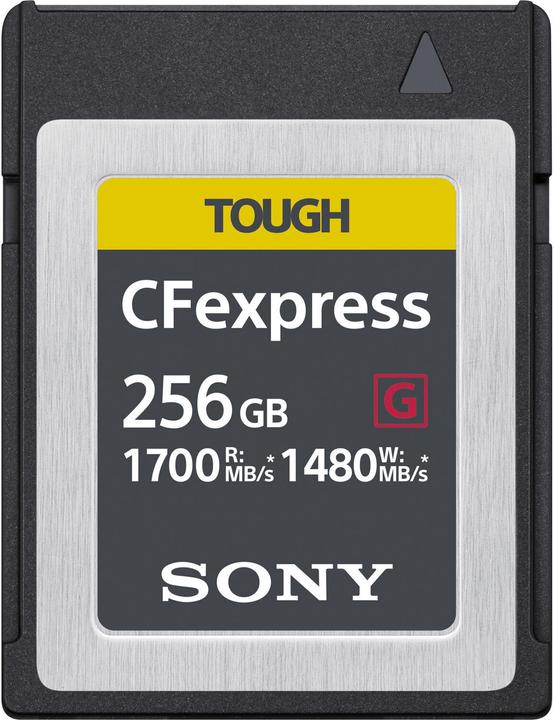

The best antidote, however, is fast memory cards (and cameras that support them). The fastest SD cards have a write speed of 300 MB/s. CFExpress cards today achieve 1400 MB/s. These values are not achieved in practice, but with the moderate file sizes of a Canon EOS 1D X III, this card speed is enough to never fill the buffer memory.

What else can slow down the speed

Battery capacity

The amount of power available can have an influence on the continuous shooting speed. Some cameras are a little faster if you use them with a battery grip with additional batteries. Conversely, the camera can also slow down when the battery is half empty.

Overheating

When shooting continuously, the camera processor has to work just as hard as when recording video. If the camera is already hot, it may reduce the continuous shooting speed to protect the electronics. This can happen if you have filmed a longer video shortly beforehand.

Flash

An electronic flash operates with a voltage of several hundred volts. The capacitor needs some time to recharge between two flashes. Flash and fast continuous shooting do not go together. Use a continuous light instead.

Slow shutter speed

The most banal thing at the end: Short intervals are not possible with long exposure times. If you expose at 1/20 second, you can never take more than 20 pictures per second. Possibly even significantly less, depending on how much time the camera needs between two photos.

As fast as the weakest link

Numerous things can slow down the continuous shooting speed. It is only ever as fast as the slowest particle in the process. But it is not so important whether a camera shoots at 10 or 20 fps. It is much more important that the images are good. That's why 10 frames per second with a mechanical shutter and tracking autofocus are worth more than record values achieved in the simplest way.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.