These two guys have built a scart switch for retro consoles

Anyone who owns old games consoles will be familiar with the problem: countless cables, all tangled up in each other and practically out of reach behind the TV furniture. Two hobbyists no longer wanted to put up with this and have developed their own scart switch.

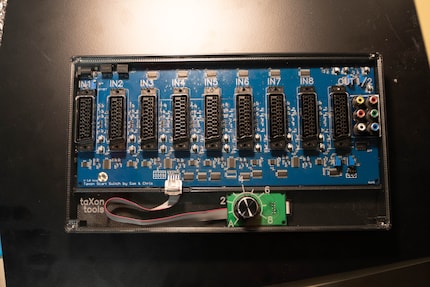

The transparent Plexiglas cover allows a direct view of the innards of the Taxon Scart Switch. Because Christopher Holder and his mate Samuel Gasser have nothing to hide. They are proud of their development. They have acquired all the knowledge themselves. "During my training as a computer scientist, I had to develop my own circuits. But never anything as complex as a scart switch," says Christopher with a laugh.

Switches or multiple plugs for the long outdated Scart TV connection already exist, but not in the quality that Christopher and Samuel would like. "There are scart switches that work like old network hubs. The stronger one wins. That can be dangerous," explains Christopher, who works as a software engineer at digitec. Old consoles such as the Super Nintendo draw power via the Scart connection even when they are not switched on. "You could easily connect a 12V light bulb to such Switches." A cheap Switch offers no security and can damage other consoles. "Our switch is secured in such a way that no signal is passed on - regardless of whether it is switched on or off," Christopher assures us. He should know. There are more old games consoles in his flat than me and all my friends used to own together.

"Then we'll just do it ourselves."

Despite this, Christopher and Samuel, who also works in software development, initially had doubts as to whether the effort would be worth it. "We asked ourselves: Who wants a scart switch these days? But at some point after a beer, we said to ourselves, let's do it now." Although neither of them is an electronics engineer, the two friends were not intimidated. They bought a circuit diagram for a two-port switch on the Internet for one franc. "We then modified the switch to suit our needs. At the beginning, I hardly understood anything and had to catch up on a lot of knowledge," says Christopher.

The switches are produced in an improvised basement workshop in the middle of a residential neighbourhood in Spreitenbach. They have now optimised the manufacturing process so that they only need around three hours per device. "But then we produce 20 of them at once," says Christopher. Getting there was and still is associated with a lot of failure.

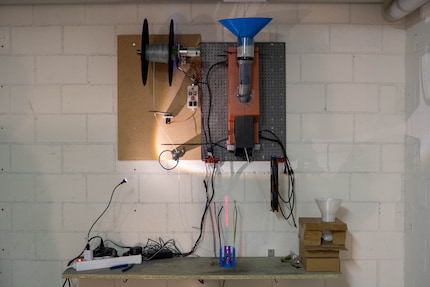

As I enter the small basement room, the home-made 3D printer filament machine is running. Around eight bags of raw material are stacked up next to it. "Finished filament costs around 30 francs per kilogramme. If we make it ourselves, the price is around three francs," says Samuel with satisfaction. The machine also runs when the two are not in the workshop. When they returned one evening, parts of the machine had self-destructed and nothing was working. "We have now installed a fuse to prevent this from happening again."

The pellets for filament production have to be dried before they can be used. Another thing the two had to learn. "The first time we tried it, we filled the pellets directly from the bag into the machine. Not a good idea," as Samuel now knows. Because the pellets absorb moisture, the filament first inflates and then collapses again. "You can throw the result away." In the meantime, they have switched from the sandwich toaster to a small pizza oven to dry the pellets. They have also set up an air dryer and a measuring device that monitors the humidity in the workshop.

Christopher and Samuel print the housing from the filament. Each of them is responsible for certain colours. The model that has just been ordered is to be black. "We've also received an order in gold, although we actually only offered that as a joke," says Christopher with a laugh.

A not entirely automatic machine

The circuit board is the heart of the switch. They have it manufactured in China. However, they had to draw the template themselves. For a newcomer like Christopher, it was quite a challenge to design the plans for the 8-port switch. "Most of the instructions talked about two layers of conductors. Our board consists of four." Compared to a PC mainboard, which consists of 16 layers, this is nothing, but it still gave him a headache.

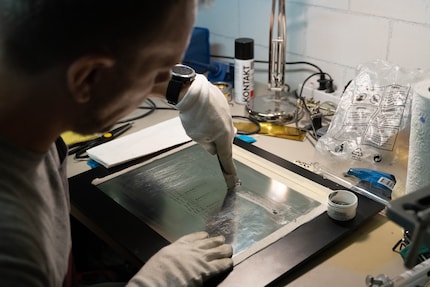

Samuel applies a wafer-thin layer of solder paste to the circuit board. He then moves on to the pick and place machine. This inserts the more than 300 components into the board automatically. "They say it's automatic, but I'd say it's semi-automatic at best, as you'll soon realise," says Christopher with a meaningful grin. And indeed, after just a few work steps, the robot arm moves back and forth without gripping a component. So Christopher has to manually align the components, most of which are wound on spools, so that the machine can grip them. Some components are only a few millimetres in size and can barely be gripped with the tweezers. Without any incidents, the process takes around ten minutes; during my visit, it took a good 20.

An oven with a diesel generator

Once the circuit board is fully assembled, Christopher checks that everything is really in place and that every part is correctly positioned. "Now comes the not so environmentally friendly part." With this sentence, he pulls a thick power cable out from under the table and runs it outside - to a diesel generator. Because the next step is to "bake" the circuit board. The device for this draws a full 16 amps. Because no socket in the building supplies that much power, a generator was needed. "I didn't tell Samuel about it when I bought the machine because I knew he would have been against it otherwise," says Christopher with a grin.

To prevent them from suffocating in the cellar, they push the 90-kilogram appliance out of the cellar in front of the apartment block. The exhaust pipe of the baking machine is held in the small cellar shaft for the ten minutes that the process takes. "As soon as the spiders start to move, we know that the baking process has started," says Samuel.

A short "ding" like a microwave signals the end of the baking process. After that, the Scart plugs and a few small parts have to be soldered before the switch can be assembled and tested for functionality. This is where the next problems initially lurked.

No compromises on image quality

In addition to safety, image quality is a crucial aspect. In the beginning, they had the problem that the Switch did not reproduce the image cleanly. "With 'Sonic 1', you could see it very clearly in the lettering on the start screen. There was then an extra line." The two had various assumptions as to what could be causing this. And with the zeal of ambitious hobbyists, they bought the new components directly in the quantities they needed for the next production run. With no guarantee that it would work. "We don't know exactly which fix helped 100 per cent, but the calculation worked out."

The blue model they gave me to test is already the fourth version. I connected a Super Nintendo, the NES and a Sega Mega Drive to it. If several consoles are switched on at the same time, the signal of the device plugged in furthest to the right is shown. Alternatively, I can use the rotary switch to switch back and forth between the different consoles. And all I had to do was connect a cable to the TV. This convenience was the driving force behind the project, says Christopher. "You should see my living room. I've got a whole shelf of consoles. Do you think I want to climb behind the shelves all the time? And then I never know which cable belongs to which console."

The two sent the Switch to a renowned blogger in the USA at the same time. He compared the device with two competitor products and identified potential for improvement. The feedback is already being implemented in all newly manufactured units. "Unlike the competition, however, our Switch is available for delivery," emphasises Samuel. And it has also recently been available from digitec.

Being the game and gadget geek that I am, working at digitec and Galaxus makes me feel like a kid in a candy shop – but it does take its toll on my wallet. I enjoy tinkering with my PC in Tim Taylor fashion and talking about games on my podcast http://www.onemorelevel.ch. To satisfy my need for speed, I get on my full suspension mountain bike and set out to find some nice trails. My thirst for culture is quenched by deep conversations over a couple of cold ones at the mostly frustrating games of FC Winterthur.