Background information

How the "Fairchildren" founded Silicon Valley

by Kevin Hofer

A whole new world opened up for electronics hobbyists in the early 1970s: thanks to Intel, microprocessors became accessible to a wider public. It was the tinkerers and enthusiasts who laid the foundations for the PC's triumph.

With the Intel 4004, the chip giant laid the foundations for the PC revolution in the 1970s. The team leaders at Intel were aware of this, but the leading computer manufacturers of the time were not. Despite the trend towards cheaper, faster and more powerful devices, few could imagine a market for personal computers even after the invention of the microprocessor.

Big computer companies such as IBM repeatedly missed the opportunity to make PCs socially acceptable at the time - and to make a huge business out of it. Instead, the new generation of microcomputers or PCs emerged from the minds and passion of electronics hobbyists and small entrepreneurs.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, advances in semiconductor technology were recognised and fuelled the computer grassroots movement. Lee Felsenstein started the Community Memory Project in 1973. He developed a multi-user information board system for it using the SDS 940 mainframe computer, which he installed in shops around Berkeley. Community Memory was based on the ideals of decentralisation and open access. It was one of the earliest online communities. This movement was a sign of the times, an attempt by computer-savvy people to give the general public access to a public computer network.

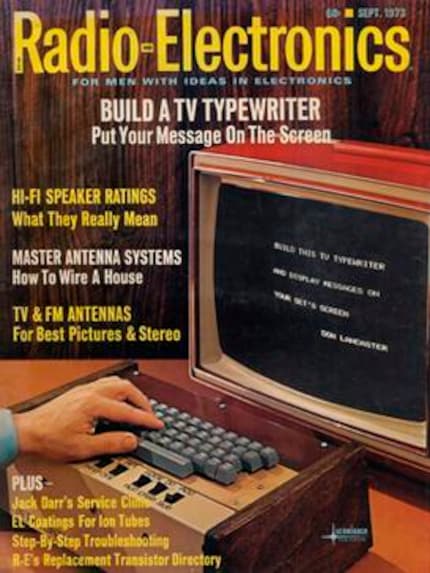

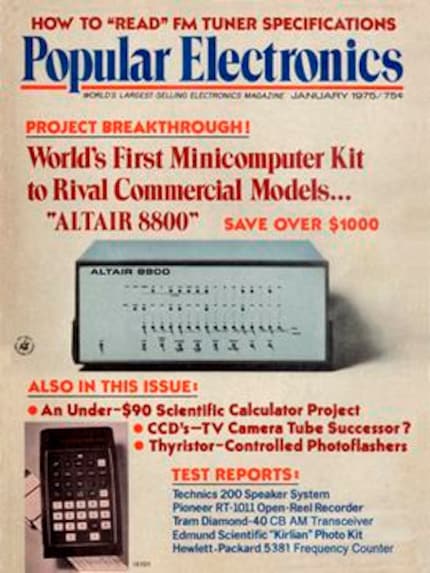

Engineering and electronics hobbyists were frustrated because access to computers was difficult. This was expressed in electronics magazines in the early 1970s. Magazines such as "Popular Electronics" and "Radio Electronics" contributed to the idea that PCs were needed. In the San Francisco Bay Area and elsewhere, hobbyists organised computer clubs. There they discussed how to build their own computers and helped each other.

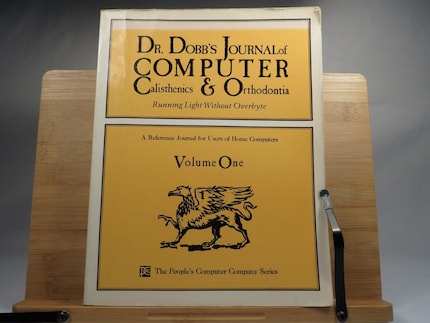

Dennis Allison wrote a version of BASIC for these early personal computers. Together with Bob Albrecht, he published the code in 1975 in a newsletter entitled "Dr Dobb's Journal of Computer Calisthenics and Orthodontia". The name was later changed to "Dr Dobb's Journal" and was published monthly until January 2009.

In September 1973, Radio Electronics magazine published an article by Don Lancaster. In it, the author described how he built a "TV typewriter": For around 200 dollars, early microcomputer users could thus build a terminal and turn a standard television into a display. Professional terminals cost over 1000 dollars at the time. Lancaster's article influenced a whole generation of computer hobbyists and contributed to them venturing into home-built computers.

Without a company selling the hardware, it wasn't possible after all. Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems, or MITS for short, was a company with a tiny office in a shopping centre in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The company had started out in 1968 selling radio transmitters for model aeroplanes. In the early 1970s, the company expanded to offer kit computers. This step almost cost MITS its head and neck: at the same time, larger manufacturers such as Hewlett-Packard and Texas Instruments were flooding the market with mass-produced computers. This meant that the average cost of a computer fell from several hundred dollars to 25 in 1974. MITS was on the brink of extinction.

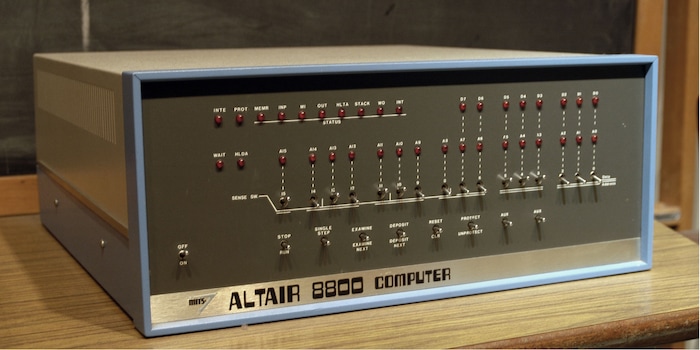

In search of a new product, MITS came up with the idea of selling a computer kit. And so the Altair was born. The kit contained all the parts needed to build the Altair 8800. The part cost just under $400, only slightly more than the Intel 8080 microprocessor - the successor to the Intel 8008 - that powered it. Popular Electronics magazine printed the Altair 8800 as a cover story. As a result, MITS sold hundreds of kits and the company was saved.

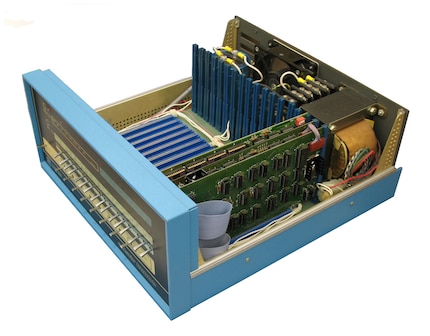

Surprised by the large number of orders, MITS could only supply a bare-bones kit, as any assembly would have made the promised 60-day delivery time impossible: housing, CPU board with 256 bytes of memory and a front panel. The early machines were not particularly reliable. Getting them to work at all required many hours of assembly by electronics experts.

The Altairs were blue boxes measuring around 43×46×18 centimetres. There was no keyboard, no terminal, no punched tape reader or printer. There was also no software at all. Programming was done using assembler language. The only way to enter commands was to set toggle switches on the front panel - step by step. LEDs were used for the output.

The Altair 8800 piqued people's interest. In Silicon Valley, members of the fledgling hobby group Homebrew Computer Club gathered in front of the Altair. Member of this club: Lee Felsenstein. They compared digital devices they were constructing and discussed the latest articles in electronics magazines.

The Altair was hardly a revolutionary invention along the lines of the transistor, but it promoted far-reaching changes that gave hobbyists the confidence to take the next step.

Some entrepreneurs, particularly in the San Francisco Bay Area, saw opportunities to build add-on devices or peripherals for the Altair; others decided to develop competitive hardware products.

This new market led to a call for standards: different machines can use different data paths or buses. Peripherals built for one computer may not work with another. The Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers developed the S-100 bus standard. This was open to all and became ubiquitous in early personal computers.

Standardisation on a common bus helped expand the market for early peripheral manufacturers, spurring the development of new devices and freeing computer manufacturers from the cumbersome need to develop their own proprietary peripherals.

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all