From the abacus to the arithmometer: The history of computing, part 1

Computers are omnipresent today. With smartphones, wearables, etc., we carry them with us all the time. However, it has been a long, rocky road to get here. In the first part of the history of computing, you can find out more about Abaki, the first calculating machines and the arithmometer.

A computer automatically calculates routine tasks. Right? Wrong! Calculation is more than just a mathematical process. Many everyday actions are subject to complex calculations that are not typically associated with maths. For example, walking around your room requires complex, subconscious calculations. Computers can now also do this in the form of robots.

The history of computing is linked to learning processes. As the first part of this historical outline will show, the inventors first had to realise that the predecessors of computers could do more than just one calculation. The story of how these challenges were solved is the history of computing.

Our journey through time begins with the Babylonians. Merchants needed a tool to calculate their purchases/sales or to manage their stock. This is where the abacus came into play.

Abaki

The abacus is a simple device for calculations that is probably of Babylonian origin. The predecessor of modern computers and calculators was therefore invented around 2500 years before our era. The earliest abacuses (abacuses are also correct) were probably not used for calculations, but for writing. They were simple tablets on which the Babylonians scattered sand to write on.

The word "abacus" probably comes from the Hebrew "ibeq", which means "to wipe dust". Ibeq was then changed by the Greeks to "abakus", which means "tablet". With the change in meaning, the abacus became exclusively a calculating aid.

This usually consists of a rectangular frame that is connected horizontally with parallel rods. Spheres are attached to these. The individual bars represent different units or weights. This allows arithmetic operations to be carried out, which are necessary for buying/selling or bookkeeping. The following video explains how the abacus works.

The abacus is a digital device in that it represents values abstractly. A sphere is either in one predefined position or another.

Abacuses have simplified calculations. But they had their limits. Complex calculations took a long time and certain things could not be calculated with them. The progress of science made new ways of simplifying calculations necessary. One of these mathematical developments that was important for computing was logarithms.

Logarithm

Mathematical calculations that correspond to the logarithm already existed in India before our era. The term was introduced by the Scottish mathematician John Napier in 1614, who developed the logarithm to simplify the multiplication of multi-digit numbers. Logarithmising makes it possible to replace multiplication with addition, division with subtraction, exponentiation with multiplication and root extraction with division.

Fun fact about Napier: It was often said that he was a magician and practised alchemy and necromancy. For example, he was said to have enchanted a flock of pigeons that ate his grain. His neighbour, who owned the pigeons, told him: "Catch them if you can." The next day, the pigeons lay unconscious on the ground. According to tradition, Napier soaked the grain in wine. The pigeons probably needed to cure their intoxication.

Be that as it may, Napier began working on logarithm tables in employees of the English mathematician Henry Briggs. Briggs continued this work after Napier's death in 1617 and by 1624, tables for the logarithms of the numbers 1 to 20,000 were available. This made complex calculations easier for the scholars of the time.

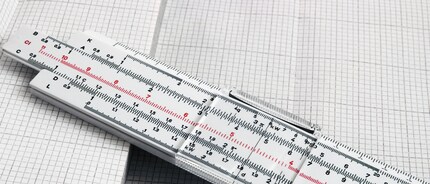

What does this have to do with computing? The transformation of multiplication into addition has made it easier to automate calculations. Analogue calculating machines based on Napier's logarithms soon appeared. Around 1632, the English mathematician William Oughtred built the first slide rule based on Napier's ideas. The slide rules were subsequently optimised further and further. Like the abacus, the slide rule was therefore widely used.

However, analogue calculating machines were not the only ones to be used. The first mechanical calculating machines were developed around the same time as the slide rule.

First calculating machines

Source: Wikipedia

In 1623, the German astronomer and mathematician Wilhelm Schickard developed the first mechanical calculating machine. It could be used to add and subtract six-digit numbers. Schickard wanted to build a calculating machine for Johannes Kepler, the discoverer of the laws according to which the planets move around the sun. However, this fell victim to a fire before it was completed. Even the plans for the machine were lost in the meantime. Schickard and his family disappeared during the Thirty Years' War. A working replica was not built until 1960.

The first mass-produced simple calculating machine was the Pascaline. Invented by Blaise Pascal around 1642, it could only add and subtract. Pascal invented the machine for his father, a tax officer, to make his work easier. He produced over 50 copies.

Source: Wikipedia

The Pascaline was further developed by the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz. With Leibniz's calculating machine, which he invented in 1671, it was possible to multiply. It was based on the decimal system. Incidentally, Leibniz was an advocate of the binary system, although his calculating machine was not based on it. According to Leibniz, binary numbers are ideal for machines as they only require two digits. Leibniz therefore realised early on how electronic computers could work best.

Source: Wikipedia

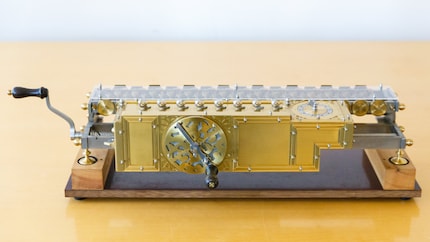

For a long time, calculating machines were the preserve of the few. With the first industrial revolution, it became necessary to perform repetitive tasks as efficiently as possible, i.e. to mechanise them. It therefore made sense to automate calculations as well. In 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar built the arithmometer. It became the first commercially mass-produced calculating machine. Based on Leibniz's calculating machine, it was capable of addition, subtraction, multiplication and, with a trick, even division. It was very popular and was sold for around 90 years.

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all