From the Emmental into the world

PB Swiss Tools is the only Swiss tool manufacturer that still produces everything in Switzerland. Why this is worthwhile is mainly due to the commitment of its employees – and a few robots. A trip to the Emmental.

Bulky 18th-century wooden houses with gable roofs nearly brushing the ground look like dark patches on the green meadows. It’s a similar sight to the skins of the cows grazing on them. Bales of hay are lined up neatly are dotted in between. Tractors chug along the country road next to them.

Here in the Emmental, farming has a long tradition that’s still very much alive. This is in spite, or maybe even because, of the fact there’s an industrial building plonked right in the middle of this idyll – the headquarters of PB Swiss Tools.

From nose rings to traumatology products

The history of the family business goes back to 1878. It all began as with a small forge producing nose rings for oxen in the village of Wasen in Emmental. When the second generation took over, PB Baumann GmbH was officially established in 1918. During World War II, the company produced hand tools for the Swiss Army. In the early 50s, the company was the first in Europe to produce the screwdrivers with the iconic red translucent handle that we all know today.

Even today, the tools are exclusively manufactured in the Emmental, namely in Wasen and Sumiswald. And it’s also in the Emmental that I meet up with Christian Baumberger, Sales Director for Germany, Austria and Switzerland. He gives me a tour of the factory. «We mainly produce classic hand tools such as screwdrivers, hammers and offset screwdrivers. But for a few years now, we’ve also been producing medical products for traumatologists and orthopaedists,» he tells me. «It wasn’t a huge leap. Everything needs to be durable, precise and, above all, made of steel.»

A whole year’s supply of the raw material is stored between orange pillars and large windows, stacked on green shelving that’s missing shelf boards. There’s a good 500 tons of spring steel, alloyed by a steel mill in Germany and Italy, and exclusively made for PB Swiss Tools according to a special recipe. «Thanks to these reserves, we can produce our hand tools for at least a year, even if we’re faced with supply issues,» says Christian.

Signs with motivational mantras dangle from the ceiling, swaying in the breeze created by an oversized fan. They were thought up by the team and meant to express unity and appreciation. As a large employer in the region, these values are important at PB Swiss Tools. «The majority of employees are from the Emmental and are proud that their products are shipped all over the world.» And this isn’t about to change anytime soon. After all, the tool manufacturer depends on it. «Skilled staff isn’t necessarily ready to up and leave Zurich or Basel for the quiet, remote Emmental,» he says.

Fluctuation towards zero

Polymechanic Nathan Reist, who works in metal cutting, has had the PB Swiss Tools building in Wasen within view since he was a schoolboy. «I could see it from the schoolyard. Already back then, I knew I wanted to be in there one day.» It’s been almost six years now that he’s been seeing the inside of the building every day. This makes Nathan almost the youngest on duty here. Take his colleague Roland Rubin, for example, who’s standing at a high-tech CNC lathe currently producing the heads for the most expensive standard product, the recoilless hammer. He’s been here for 44 years. He started at PB Swiss Tools directly after his basic military training and will retire in November. «Then, I finally want to travel extensively. I would have loved to take the Transsiberian Express from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok. Unfortunately, that probably won’t be possible at the moment. Maybe I’ll do Alaska or Patagonia instead.»

Nathan, on the other hand, prefers to look back rather than at what’s immediately ahead. His grandfather already worked here part-time. He was a farmer full-time and made a little money on the side working for the tool manufacturer: «He had a big toolbox filled with screwdrivers, offset screwdrivers and hammers from PB Swiss Tools at his place.» Even today, there are some farmers who work here. The company says it’s important to them to support local traditions. «But the majority do a bit of farming and earn the main part of their income here,» Sales Manager Christian adds.

The slotted screwdriver aka multi-tool

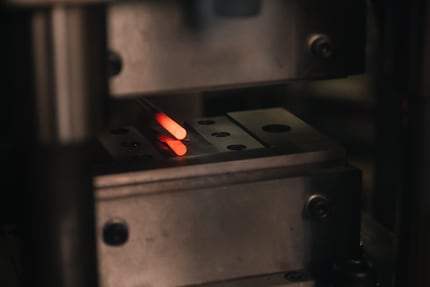

As did Urs Aeschlimann. He spends 80 per cent of his time die cutting tools and 20 per cent working together with his wife on their own farm. His machine is working on size 4 slotted screwdrivers. They’re being heated to 900 degrees, smoothed, punched and sharpened. «Many people think that there are only Torx these days. But the slotted screwdriver is still our best-selling product», says Christian. «Almost every craftsman has one in his trouser pocket: for levering, chiselling, even weeding. Even back when I was training to be a motorcycle mechanic, I used the slotted screwdriver all the time,» Urs confirms, while I’m literally hanging onto his every word to understand what he’s saying. The die-cutting machine gives off a low yet simultaneously piercing rattle. The press next to it taps out a dull industrial rhythm. My head’s already throbbing after less than two hours in the factory.

«I normally wear hearing protection, otherwise I’d be yelling at my wife in the evening,» Urs chortles. He turns off the machine to better explain its inner workings to me. «Currently, it takes me about four hours to make all the settings for a new series. To speed up this process, there’s a new machine where you can save the settings.»

Robots for efficiency

Automation is an important at PB Swiss Tools. «We’re the only tool manufacturer that produces entirely in Switzerland. To remain competitive, we need to be efficient and sustainable,» says Eva Jaisli, the fourth-generation CEO who’s been running the company for more than 25 years. «That’s why, back in 1982, PB Swiss Tools was the fourth company in Switzerland to introduce industrial robots in production.»

Meanwhile, in addition to the classic fenced-in robots – who’d just knock down anyone who got too close – there are also collaborative robots. Christian explains: «They work hand in hand with the employees and are much easier to instruct. Take the bending machine, for example.» He points to a one-armed robot that’s working on large Allen keys to give them their typical shape. Close-by is where Thomas «Tömu» Fiechter sits. He carries out the same job manually. «I’m bending 5,000 units of the 90°–100° model. You can use it at a right angle and lift it. This provides enough space to move your hands even when you’re working with shallow screw accesses.» No robot can produce tools this specialised in one go; experienced hands are needed for this.

Loyalty runs blood of Emmentalers

Because of employees like Tömu, moving production abroad was never an option, says Eva Jaisli. «Most of our employees are rooted in the region and proud of the products they create. Their commitment to the company is at the core of our quality and innovation.» This loyalty seems to run in the blood of the people of Emmental. At least this is what author Jeremias Gotthelf already observed in 1840: «The Emmentaler is similar to his landscape. His range of vision is not wide, but he looks at close things cleverly and precisely; he does not grasp the new quickly... but what he has once grasped he holds onto with wonderfully tenacious strength.»

Things seem to be paying off for PB Swiss Tools. Business is going well. 2021 was a record year for the company, in part because of the pandemic. «Everyone wanted to work on their homes and stocked up on tools. Not just in Switzerland, but in almost all of the 85 countries where we sell our products,» Christian says. He adds that there’s so much to do at the moment that there are few special requests small-batch special productions; it’s mainly bestsellers keeping the departments busy.

These include Torx bits, which are being sharpened or trowalised, to put it in technical terms. If it weren’t for the odd metal part sticking out from the drum, the machine might also be spotted in a sweets factory. Those pink pyramids aren’t Haribo Primavera Strawberries, but standardised grinding stones. «In the past, you’d use stones from the stream that runs behind the factory,» says Christian.

Chroming to Tamil tunes

He’s particularly keen to show me the next step, as it’s part of an in-house innovation. «Our bits are colour-coded according to screw type or size for offset screwdrivers. This helps you find the right part faster.» As he says this, the third-smallest wrenches in the so-called RainBow set are currently being powder-coated in green by hand. While this is happening, the parts that aren’t getting a paint job are- being galvanised, which means nickel-plated or chrome-plated. Unlike the dyeing, this is done fully automatically. It’s the loading and unloading of the parts that require a lot of skill fine-motor skills and needs to be done manually.

For the first time, it’s neither machine engines nor the Bernese dialect echoing through the halls, but Tamil music. There are small speakers installed all along the wide window ledge. Sairaj Shanmugalingam laughs almost nonstop as he shows me his work. Each tool model needs to be attached to the red frame in a different way. Some need to be screwed in, others are clamped into place or lain down. «It can get a bit tedious with very small parts, to the point I might utter a goddammit. But even after ten years, I still enjoy doing the work.» Sairaj immediately bursts out into his infectious laugh again and turns up the music of his home country a little to finish.

It’s a different story over in quality control; a glass box a mere ten feet away. It’s where all the metal parts are checked for defects and corrected one last time, before the truck transports them to the neighbouring village of Wasen. The oldest (now modernised) machine in the factory produces the classic transparent red and green handles using the so-called injection moulding process. Surprisingly, in addition to lubricating oil, there’s also a scent of vanilla in the air. «The fragrance is added to the granules. That’s because the material – so-called acetobutyrate (CAB) – contains an esterification of butyric and acetic acid. If a classic screwdriver is left in a toolbox for a long time without any air circulating, these acids can decompose, giving the handle a whiff of urine,» Christian explains. «When Eva Jaisli took over the company, she decided to do something about it. That’s when we started adding the vanilla scent to mask the smell.»

There’s another problem PB Swiss Tools is facing with the injection moulding technology. For the first time, the much-quoted «shortage of skilled workers» is mentioned. Injection moulding engineers have gone through highly specialised training only very few people have,» Daniel explains. He’s been temporarily managing this area for a month. But he goes on to say that he’s not too worried, as relief is in sight. «Things are looking good. We'll probably be hiring a new manager soon.»

Blade finds handle

The situation is completely different one floor above in assembly – Daniel’s core area. With 27 permanent employees, nine temps and usually two to five employees in an occupational reintegration programme, the team is fully staffed. This is where offset screwdriver sets are assembled and packed; where torque screwdrivers with built-in electronics are calibrated, and where the handles are printed so that the brand is visible and the tool can be traced.

Once the logo, product and serial number are applied, the handle and the blade of the screwdriver are finally united. The majority are assembled through the arms of a robot. Special models require a human hand and a hydraulic press. While the employees stay in Emmental at the end of their shift and take care of their children, houses or even farms, the screwdrivers leave the multi-storey factory building, driving past the traditional scenery. They leave behind the floor-to-ceiling gable roofs and meticulously rolled-up bales of hay to start a new life in a toolbox in Zurich, Berlin or even Tokyo.

My life in a nutshell? On a quest to broaden my horizon. I love discovering and learning new skills and I see a chance to experience something new in everything – be it travelling, reading, cooking, movies or DIY.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show allThese articles might also interest you

Background information

Design made in Switzerland: 5 iconic Swiss products that play with the colour red

by Pia Seidel

Background information

Behind the scenes of Switzerland’s most renowned Asian mushroom producer

by Darina Schweizer

Background information

A reflective nation: lessons in visibility from Finland

by Martin Jungfer