Guide

What’s sampling rate got to do with quality of digital music?

by David Lee

Top devices are always eyewateringly expensive, especially audio tech. This isn’t a problem in itself, as long as enthusiasts can still hear a difference. But with progress, this is less and less the case – and our brain starts to play tricks on us.

You can get headphones for five francs. And for just a little more you already get much better quality. Paying even more, say 150 francs, really delivers phenomenal soundscapes. Same at 500 francs, even 2000 francs. Things can always get pricier.

Welcome to the high-end, where prices go through the roof. But what about actual performance?

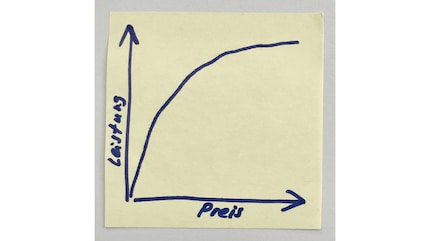

In general – not just for audio products – performance doesn’t increase linearly with price. Instead, in the upper range, prices increase disproportionately to performance. Sort of like this («Preis» = price, «Leistung» = performance):

All things considered, high-end products generally have a worse price-performance ratio than mid-range equivalents. Not that the target group cares. If you want the high-end and can afford it, you know and accept this fact. People will do anything for love – and a love of music is the strongest and most passionate relationship in the lives of many.

So far so good. If the 2000-franc headphones still sound a little bit better than the 500-franc ones and are worth it to the buyer, why not?

The problem is, at some point, more performance doesn't improve your experience. We no longer hear the difference. There are physical limits to our ability to perceive. Staying with headphones, my current test device, the Sennheiser HD 660 S2, can reproduce frequencies up to 41.5 kHz. On paper, this makes it better than my Beyerdynamic DT 990 Pro, which «only» reproduces sounds up to 35 kHz. Only, no human can hear 35 kHz. Even bats can’t: these ultrasonic frequencies aren’t even present in the most common music formats and consequently won’t be played.

In many sectors, technology has reached a point where further improvements are of no use. The resolution of many smartphones is higher than what I can see without a magnifying glass or reading glasses. Who can even fully enjoy a refresh rate of more than 400 Hz? Or over a billion colour gradations on HDR screens? I could go on listing examples.

But back to audio. For headphones, exact frequency specifications don’t play a major role, they’re not a selling point. They’ll only be included in the data sheet. A hotly debated topic, on the other hand, is sampling rates.

CDs and many uncompressed audio formats have a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. This value isn’t chosen at random: according to the Nyquist-Shannon theorem, a sampling rate must be twice the size of the highest frequency to be reproduced. CD quality thus allows the correct reproduction of frequencies up to just above 22 kHz. Perfectly adequate for human hearing. 60-year-olds hardly hear above 10 kHz, babies max out at 20 kHz.

Higher sampling rates therefore aren’t completely pointless. They don’t only allow for higher frequencies, but also more precise reconstruction filters. A reconstruction filter determines how analogue sound waves are generated from digital data. Better filters, unlike ultrasound, are at least theoretically audible.

But here, too, technical progress has long since taken care of everything. Today, even the cheapest Digital Analogue Converter (DAC) can handle sampling rates of 96 kHz. For example, this one. And the DACs built into computers are also at this level.

If you still think that’s not enough, you can get four times the rate, i.e. 384 kHz, for a ridiculous price.

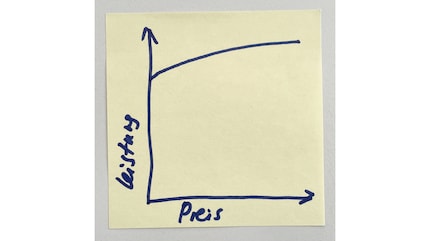

Sampling rate is only one factor of many when evaluating a DAC. But similar things could be said about bit depth and other specs. Today, DACs just don’t deliver poor sound quality any more. For this device category, I’d adjust the price-performance diagram from above as follows:

Nevertheless, you can still spend 5,000 francs or 65,000 dollars (listed price of the Boulder 2120) on a DAC. In return, you get a variety of connections, settings and additional functions. However, most of the massive extra price is justified by a promised «improved» sound. But are these improvements audible or not?

To check this, scientific blind tests are carried out. The result is almost always the same. Most people aren’t able to reliably detect different sampling rates above 44.1 kHz. Nobody hears ultrasound anyway, and the differences between modern reconstruction filters are only detectable by trained users under very specific circumstances.

This, one might think, would’ve settled the matter. But surprisingly, the opposite is true.

In a study from 2000, researchers claim to have found that although people don’t consciously hear ultrasound, they unconsciously respond to it psychologically and physically. This is difficult to prove. The findings stand on shaky ground and haven’t been verified since. But audiophiles like to hold it up as proof to this day. There’s even a buzzword for it: the Hypersonic effect.

And the filters? A lot can be criticised in the blind tests at high sampling rates. The sample tracks aren’t optimal, the volume is only adjusted by ear and not with measuring instruments and the equipment isn’t good enough to highlight any differences.

Because such objections keep being raised, new blind tests keep being developed. And at some point, after many, many studies, someone finally found out that you can hear a difference after all. In the study that found this,

however, special test signals had to be played, including white noise. With music, there’s still no definite proof.

As always with scientific studies, one can selectively pick out those that agree with one’s personal view. Another reason for why these discussions never end.

It’s practically impossible to prove that something is useless. Even if the argument is completely watertight, someone can always claim that he – or much more rarely she – hears a difference after all.

And they’re not even lying. The people who claim to hear a difference are usually being honest.

Simple technical specifications such as 96 kHz have a complex technical background that is hard for non-professionals to fully comprehend. Half-knowledge often leads to false assumptions. It therefore seems reasonable and obvious to rely on your own hearing. After all, only one thing matters in the end: whether it sounds better to my ears or not.

But it isn’t so simple. We don’t just hear with our ears, but with our noggin too. The brain fills in missing information or invents it new. If you understood a different word than the person you were talking to spoke, it was your brain that added something wrong.

The brain constantly tries to make sense of what the sensory organs provide it with. When I test two different headphones or two different DACs, my brain immediately tries to understand the difference. If it’s set on recognising the difference between a 100-franc DAC and a 1000-franc DAC, it will find it. No matter whether the ears hear anything or not. Audio expert Amir Majidimehr describes his experience very similarly in this video from minute 31 to 34.

This is why researchers use blind tests. It eliminates the placebo effect. Sometimes they’re even double-blind studies: the person who guides the subjects through the tests doesn’t know what is being tested. After all, their knowledge could unconsciously influence their behaviour and thus the subjects.

At home, I can’t perform even a simple blind test in many cases. I know which headphones I’m wearing, and that knowledge influences me. To blindly compare two DACs, I’d have to have two identical source devices and headphones, and the same music would have to be playing on both systems at the same time. And even then, I know which two devices I’m comparing and what they promise.

Similarly, many users like to write gushing reviews of audio products with at least questionable utility. As an example, I pick out the audiophile network switch from Aqvox. As Linus Tech Tips points out, Aqvox took a D-Link router, stuck a different logo on it, installed lots of Illuminati holograms as well as a quartz stone, and marketed the whole thing as an unmatched audiophile’s dream packed to the brim with Voodoo magic. Starting at 15:04, Linus explains why an audiophile network switch can’t work even as a concept.

Still, the product has many convinced fans and enthusiastic reviews to boot. It’s amazing what testers can pick out. They mention «a greater soundscape, richness of detail, dynamics and definition», «the instruments gain substance, appear more colourful and contoured. At the same time, a beautiful ambiance forms around each instrument.» But above all, «the aforementioned sonic characteristics of the AQVOX Switch are immediately audible without any major difficulties». Apparently, the new version is even better.

Both cited reviews also report an obsessive preoccupation with the equipment and contacts with the manufacturer – one tester let himself be talked into a long phone call. This procedure is the opposite of a blind test: an extensive tuning of the brain to what the company wants. Anyone who tests like this can’t claim to rely exclusively on their hearing.

Even in Linus’ blind tests, two and three out of ten test subjects, respectively, stated that they could hear a difference. Of those, however, 80 per cent prefer the unmodified $30 switch to the audiophile grade $800 switch. Just knowing that you have now switched on something that should increase the quality leads you to actually hear a change.

Where clearly audible differences disappear, psychological factors gain importance. Serious manufacturers of high-end audio face two problems as a result. First, all the effort they put in doesn’t add any clearly identifiable value. Even if the measurable performance is higher than that of the cheaper competition, it isn’t audible.

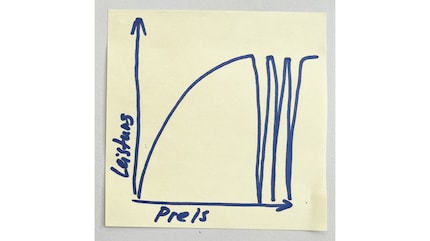

And secondly, almost worse, such a product is no longer distinguishable in effect from second-rate products. And those are a dime a dozen – for exactly this reason. The high-end industry is falling into disrepute as a result. I’ll therefore draw a third, not entirely serious version of my price-performance graph:

It’s bitterly ironic that the very products that perform the best are confused with those that don’t perform at all. No wonder the topic is polarising.

By the way, I’m currently testing an expensive DAC from RME Audio. The manufacturer makes an exceedingly serious impression, and I actually can hear a difference to my 70-franc DAC. But it’s not a blind test. Is my brain fabricating the difference? You’ll hear from me once I know more.

Header image: Amplifiers and loudspeakers at the BAV Hi-End Show in Bangkok. The Kharma Enygma Veyron 2 Diamond at the very end costs 375,000 euros. Source: Shutterstock/Brostock

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all