Mistakes are forbidden when developing films yourself

In the analogue world, there is no undo function. If you make a mistake, your stuff is ruined. This is also the case when developing a film. But once you know how to do it, it's not too difficult.

There are fewer and fewer specialist photo shops or other places where you can have your films developed. Even Ars Imago, the Zurich shop for film hipsters, doesn't have its own processing lab, but sends the films to an external lab - so you have to wait two weeks for your film.

Why not try developing your own film? The kits are not expensive. And the effort? Maybe it's too complicated for me; but to find out, I have to have tried it at least once.

The set is for black and white films. Developing them is considered easier. So I dedicate myself to black and white development. At least for the moment.

Taking photos first

Before I can think about developing, I first need a fully loaded film. My developing set is for black-and-white film, but my camera - a Nikon F90 - has a 36 film in colour, which is only a third full. So I practically have to fill two films before I can get started: The old colour film and the new black and white film, an Ilford HP5.

This is a double change from what I'm used to: firstly from digital to analogue and secondly from colour to black and white. As I want to end up with something of lasting value from the experiment, I first give some thought to how and what I want to photograph.

The images by Joel Tjintjelaar awaken my desire for black and white. I'd like to go in that direction a little, even if I'll never manage it. Reflective skyscrapers, architecture in general, in the end I even try something with long exposures and ND filters. I always photograph the same thing with a digital camera so that I at least have a rough idea of the exposure time.

When I have the film full, I watch a few YouTube videos on the topic of developing and study the instructions. I quickly realise that it is by no means certain that I will succeed in developing the film at the first attempt. I don't dare expose my photos to this risk. After all, I have put a lot of effort into it. Instead, I put another film in the camera and take 24 pictures, which wouldn't be such a shame if they were lost.

The material battle

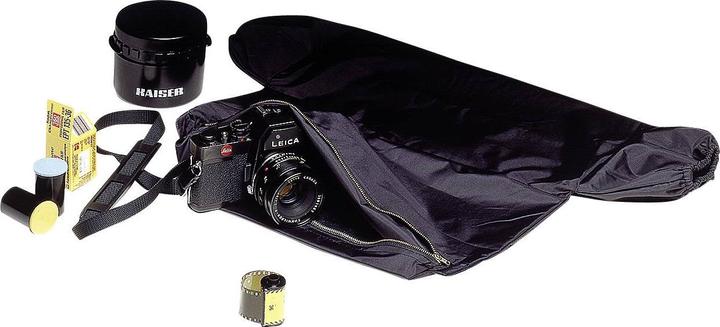

This is just the beginning of the preparations. First, I order the negative lab kit. However, it doesn't contain all the ingredients I need. In particular, the chemicals are missing. I make it easy for myself here too and order a starter kit that contains all the chemicals: developer, stop bath, fixer and wetting agent.

Ilford Simplicity Analog-Film Kit

Stop bath, Negative developer, Fixing bath, Wetting agent, Other Chemistry

To mix the chemicals, I need several measuring cups. Because I don't want to use the same ones I use for cooking, I have to buy new ones. Something for stirring that doesn't come from the kitchen would also be good. I also get a canister of distilled water. Some photographers recommend this because the water hardness is always the same and the results can be reproduced better. But you can also use tap water.

Rubber gloves should prevent fingerprints on the negative strip, and you should also have a pair of scissors ready in case the film needs to be cut or trimmed.

A so-called change bag is also recommended. This is a large black bag that is guaranteed not to let any light in and has two access points for your hands. Because part of the film processing has to be done in complete darkness. As there is a windowless storeroom in my flat, I think I can do without it.

The plan

Two things make film development tricky for a beginner. Firstly, the film has to be removed from the capsule in complete darkness and placed in the developer can. Secondly, a precise time schedule must be adhered to when developing the film. There is no time to take a break to think about what to do next.

This means that you need a very precise plan in advance of what you want to do and in what order.

This plan looks like this for me:

Prepare the "darkroom": Lay out the film, developer can with spool and lid, scissors and rubber gloves neatly so that I can feel everything in the dark.

Open the film capsule: Open the film capsule in the dark to remove the film. There are various methods for this. The most elegant is with a special film capsule opening tool. Since I don't have that, I solve the problem in my favourite way: with brute force.

Wrap the film into the spool: Push the beginning of the film into the designated position on the spool. The film should be transported into the spool by moving the two halves of the spool back and forth.

Close everything: Place the spool with the film in the can, screw the can shut. I don't need to put the cap on - the can is light-tight as it is. It has to be, because liquids have to be emptied in and out several times during development.

Mixing the developer: The chemicals are available as a concentrate and must be diluted with water. According to the packaging, the ratio for my developer is 1:9, but this is not enough for two development runs. I found an instruction at Ilford, according to which it can also be diluted in a ratio of 1:14. The development time takes longer. So I take half of the developer (30 ml), dilute with 14 parts water (420 ml) and put the whole thing in a measuring jug.

Mix the remaining chemicals: The Ilford starter kit works by adding all the chemicals to 600 ml. This is practical in that you don't have to measure the chemicals separately, but can mix everything directly in the measuring cup. However, this is only enough for one solution. Unlike the developer, I don't care about the stop bath and the fixer, as both of these solutions can be used several times. So empty both packs and top up to 600 ml.

Then add the wetting agent. This is something like liquid soap without flavouring and is intended to prevent stains and streaks during drying. I simply add a splash. I use tap water for the wetting agent.

Development: The chemicals are ready, now it's time to get started. I take the can with the wound film out of the darkroom, open the cap and pour in the developer. The developer then has to work for a certain amount of time, in my case 11 minutes. At the start of each new minute, I have to tip the can upside down and back again four times. Then tap the can to release any air bubbles from the film.

Stop: Pour out the developer and pour in the stop solution. This should remain in for around one minute, then pour out as well.

Fixing: I have not found such precise instructions for the fixer as for the developer. Ilford states 2 to 5 minutes, without precise tilting instructions. I tilt using the same method as with the developer.

Watering: pour out fixer, pour in water with wetting agent, tip five times, pour out, new water, tip ten times, then again with twenty times.

Hanging and drying the film: I hang the film on the shower rail in the bathroom. The upper clip holds the film, the lower one serves as a weight so that the strip stays straight and dries better. The water can be wiped off with the rubber pliers, which are also included in the set.

The result

The plan worked except for a few minor details. Rewinding the film worked surprisingly well. The only problem was that I couldn't find the rubber gloves in the dark. I'll have to place them more carefully next time.

The liquids that I poured into the can were slow to drain. This made the timing a little imprecise. Fortunately, I had such a long development time of 11 minutes that a few seconds more or less didn't matter.

I'll never forget the great moment when I pulled the film out of the spool and saw it: There are actually pictures on it! So it worked. At the time, I couldn't see how good the photos had turned out. Let them dry first, scan them later.

When I scan the images, I realise that the quality of the images seems to be okay in terms of exposure and sharpness. However, a white stripe runs through part of the film, always at the same height. This doesn't seem to have anything to do with the developing process, because the streak can also be seen on the light-insensitive parts of the film. Where it comes from remains unclear.

In addition, some of the images have stains and discolouration. This could be soap residue from the wetting agent.

The second attempt

On the second attempt I change a few things:

- I use a change bag after all.

- I use a funnel to pour in the chemicals. This allows the liquids to be poured in much more quickly and the timing is more precise.

- I only add wetting agent during the final soak, and even then relatively sparingly. This way there should be no soap residue.

- I wet the squeegee with warm water beforehand. According to some forum posts, this can help to prevent damage and residues.

I use the stop bath and fixer from the first time. I mix the developer again.

The result is better this time. No strange streaks and spots. The photos, especially the long exposures, disappoint me a little, but that has nothing to do with the developing. Rather with the lighting conditions when taking the photos.

The fact that the photos do not show more details is also not due to the development. Even when comparing with the Nikon ES-2 system, I realised that the sharpness delivered by the scanner is not the best.

In addition, it is a 400 ISO film, which is relatively coarse-grained due to the higher sensitivity.

This makes you want more

Even if it doesn't seem like it at first, developing black and white film at home is not rocket science and, with a bit of luck, will work the first time. Nevertheless, I would recommend that you start with a film that wouldn't be too bad if it gets damaged during development.

I can recommend the negative lab you used. Looking back, I would no longer use the complete kit for the chemicals, but buy the chemicals separately. On the one hand, you can only develop two films with the kit, and it's too expensive for that. On the other hand, the components of the kit are used up at different rates.

I've got an appetite for more. I still have a black and white film with 3200 ISO speed lying around, I'm very curious to see what's possible with it.

The weakest link in my chain to the finished image is currently my Epson Perfection V600 scanner. I assume that I could massively improve the quality of the self-developed images with a really good film scanner. An exciting alternative would be analogue exposure on film paper. I always find it a bit strange to take analogue photos only to end up with a digital image.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.