Now it's going digital: History of computing, part 3

We have already travelled over 2000 years in our series on the history of computing. Now we are diving into the digital age. In this part, you will learn all about the invention of the modern computer.

Two pieces of research were relevant to the breakthrough of the computer. On the one hand, Vannevar Bush's differential analyser and Howard Aiken's digital computer.

Bush developed the first modern analogue computer, the differential analyser, at MIT in 1930. This could be used to solve differential equations. The scope of the machine, like that of all analogue devices, was limited to this one task. Nevertheless, it is still used in analogue or hybrid computers. Especially for the simulation of complicated dynamic systems such as commercial aviation or in nuclear power plants.

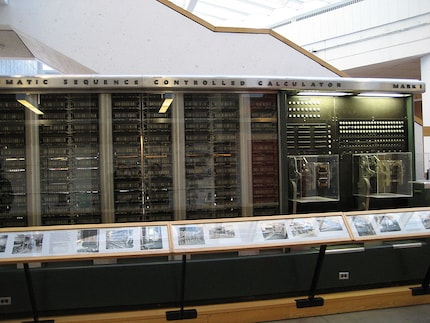

In contrast to Bush, Harvard professor Howard Aiken developed digital calculating machines. From 1937, he drew up plans for four calculating machines of varying degrees of sophistication. The Harvard Mark I was still mainly mechanical, while the Mark IV was completely electronic. The machines were huge. The Mark I was around 15 metres long.

Source: wikipedia

The Turing machine

As a maths student at Cambridge University, Alan Turing was interested in David Hilbert's formalist view of mathematics. According to this, every mathematical problem can be solved with an algorithm. For Turing, this meant that computing devices could theoretically solve all mathematical problems.

Turing set about the theoretical development of such a machine. He worked out the foundations for a universal computer. It was important to him that these computers were not limited to arithmetic. Among other things, they should also be able to display letters. Turing believed that everything could be represented symbolically. Even abstract mental states. He was also one of the first to consider artificial intelligence to be possible.

The influence of Turing's theoretical work was marginal at the time. What was important was that he inspired people to believe in a universal computer.

Pioneering work and war research

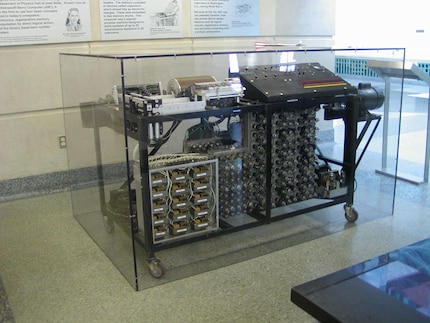

The first specialised electronic computer was probably built by John Vincent Atanasoff at Iowa State College between 1937 and 1942. The Atanasoff-Berry Computer, or ABC for short, consisted of 300 electron tubes and capacitors, among other things. It used a binary system and logical operations. Punch cards were used for input and output. However, development was discontinued due to the Second World War.

On the one hand, computer projects were cancelled. On the other hand, certain projects were subsidised during the Second World War. In England, the cracking of codes or ciphers was the impetus for computer research. The project was called Ultra and was top secret.

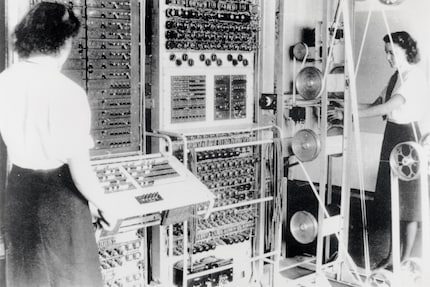

Colossus

Source: wikipedia

Under Sir Thomas Flowers and with the help of Alan Turing, Colossus was developed until 1943. It consisted of around 1800 electron tubes for calculations. Although Colossus was developed for specific cryptographic calculations, it could also be used for more general purposes. It was the first device to utilise electronics for computation on a large scale. Flowers recognised the importance of storing data electronically

.

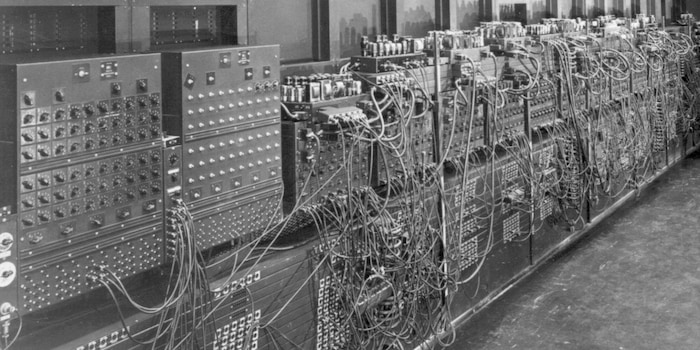

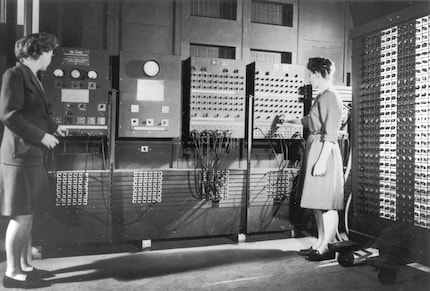

ENIAC

In the United States, research was carried out into computers for calculating artillery distances. The goal was a completely electronic computer. Employees began working on ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) in 1943, communicating with the computer via circuit boards, i.e. electronically. This meant that instructions could be read more quickly than from mechanical punched cards. The disadvantage was that the computer had to be painstakingly re-instructed for each new task.

Source: wikipedia

Although ENIAC was developed for a specific purpose, it was also able to solve other problems. The 15 by 9 metre machine was not completed until 1946. The war for which ENIAC was built was already over by then. The computer, which cost 400,000 dollars, was then used to calculate a hydrogen bomb.

Birth of computer science

The paper "Preliminary Discussion of the Logical Design of an Electronic Computing Instrument" by Arthur Burks, Herman Goldstine and John von Neumann is often referred to as the birth certificate of computer science. Among the principles, the researchers state that data and programmes should be stored in binary code on a memory. An important decision, because it means that a programme can regard another programme as data. This enabled complex programming languages and most of the advances in software in the 50 years that followed.

Semiconductors

ENIAC and Colossus both used electron tubes. They had no moving parts. This made them much faster than machines up to that time. Despite the enormous speed for the time, the basic architecture of the machines was not much more advanced than that of Babbage's difference machine. Both computers had the same problem: they each needed an electron tube to store one bit. For the successor to ENIAC, the EDVAC, the researchers therefore relied on delay lines. This allowed ten electron tubes to store 1000 bits. Before the invention of magnetic memories and transistors, the memory could be greatly increased in this way.

The first computer with semiconductor memory was built by Frederic C. Williams and Tom Kilburn at the University of Manchester in 1948. In the computer they named Baby, they used Williams tubes rather than delay lines. Although this type of memory is faster than delay lines, it is also less reliable.

A year later, the two researchers had converted Baby into a complete computer. Among other things, the Manchester Mark I made the combination of volatile and non-volatile memory standard in computers.

The inventors of the ENIAC and EDVAC went on to develop the UNIVAC. It was designed from the outset as a semiconductor computer and used a keyboard for input and magnetic tapes for output, among other things. The computer was intended to replace the accounting machines of the time. Thanks to the delay lines, it was relatively compact at around 4.4 by 2.3 by 2.7 metres and fitted into offices. It was therefore one of the first mainframe computers.

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all