"Ok Googoo": A brief introduction to speech recognition

Speech recognition is an old chestnut. Nevertheless, the age of intelligent assistants that listen to our every wish is currently being conjured up. Why should speech recognition revolutionise our lives right now? A look back helps us understand.

What would Thomas Edison say if I described him as one of the founders of speech recognition? He would probably take this statement and market it immediately. As well as being a brilliant inventor, Edison was also an unscrupulous businessman who liked to instrumentalise others for his own purposes. Nevertheless, Edison's phonograph can be regarded as one of the pioneering devices for speech recognition. It allowed sound to be recorded and played back mechanically, one of the basic requirements for speech recognition.

But enough of the history lesson. You're here because you want to learn about speech recognition. With language, we humans clearly distinguish ourselves from animals. Although certain animals also communicate with sounds, we humans have the complex system of language at our disposal.

In the following, I will give a rough overview of how speech recognition can work. I will focus on the most important ones and also deliberately leave things out.

Some linguistics to start with

The phoneme or sound is the smallest phonetic unit obtained by segmentation. This can be an "a", for example. The phoneme, on the other hand, is the smallest meaning-differentiating unit of the sound system of a language. Whereas with a phoneme we are only dealing with the sound, the phoneme already has a linguistic meaning. Phonemes are the building blocks of a language.

Would you like an example? In German (and also Swiss German), the "r" is pronounced in different ways. A Thurgau native produces the phoneme at the back, a Bernese native at the front. But the meaning of "r" remains the same. The following video explains the whole thing.

We humans give meaning to speech by hearing phonemes. However, speech recognition can only perceive phones acoustically. To understand phonemes, speech recognition requires a phonetic dictionary. This goes further than simple hearing. But let's stay with hearing. This is a complex process that involves various problems:

- Side noises: It's not always quiet in the neighbourhood. There is traffic noise on the street and other people talking to each other on public transport. Hearing also always involves filtering sounds.

- End and beginning of words: Where does one word end and the next begin? If someone speaks very quickly, for example, words cannot be clearly distinguished.

- Every sound is unique. We never say the same sound twice. The differences are even greater with other people. Origin, age, gender, etc. influence the phone we produce.

- Homophones, i.e. words that are pronounced the same but have different meanings, must be differentiated (e.g. bank/bank).

- Sentences/expressions can be completely misunderstood. These can be song interrogations such as "Anneliese Braun" or "Agathe Bauer". Although these are foreign language examples, we also mishear in German (or Swiss German).

In addition, there is the syntax and the semantics that our brain uses to decode words when we hear them. Hearing is therefore a very complex process. We humans have the impression that hearing and understanding are simple. But it's not that simple.

How can computers understand speech?

I will look at four types of speech recognition here:

- Simple pattern-based search (simple pattern matching)

- Pattern and feature analysis

- Language modelling and statistical analysis

- Artificial neural network (Artificial neural network)

These build on each other. I will briefly discuss the individual points below. However, this should be enough to give you a brief overview of how speech recognition works.

Simple pattern-based search

"Please speak your policy number after the beep." Beep. "Seven, five, three, nine ..." Who hasn't heard this before? The call centre robot wants the necessary information from us before we can speak to a human. This is an example of a simple pattern-based search.

Source: Screenshot Youtube

With the simple pattern-based search, the number of selection options is very limited. Speech recognition therefore does not need to analyse syntax or understand the meaning of the sentence. It is not speech recognition in the narrower sense. The system must be able to distinguish between a limited number of sound patterns in order to work.

Pattern and feature recognition

The vocabulary for simple pattern-based searches is very limited. Early speech recognition systems were often limited to this type. They were developed for a specific area (in the example above, a call centre) and worked relatively well in their limited field. Modern speech recognition, however, is capable of understanding thousands and thousands of words. How does that work?

One possibility would be to ask someone to sit down with a dictionary and read every word in it a few times. In this way, a database could be compiled that the speech recognition system can access. Sounds complicated? It is, and extremely inefficient too.

Why should a system memorise all the words in a dictionary if these words all consist of the same phons or phonemes? The software could simply learn the phonemes and put the words together from them.

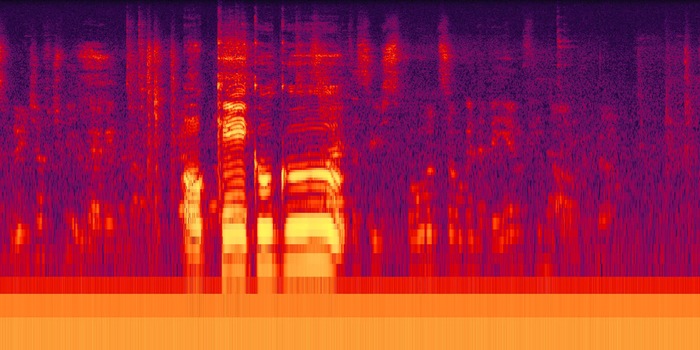

Language recognition based on this system works as follows: The recognition system listens to an utterance via a microphone. In a first step, this is digitised using an A/D converter. The data is then converted into a spectrogram and finally divided into overlapping acoustic frames. These last either 1/25 or 1/50 of a second. They are analysed and examined for speech components. The entire utterance can be split into words and the key elements can be compared with a phonetic dictionary. This makes it possible to determine what was probably said. Probable is also the keyword in speech recognition: no one but the speaker can know exactly what they meant.

In theory, it is possible to understand every utterance by filtering the individual phonemes. Instead of learning thousands of words, speech recognition only needs to know around 40 phonemes (in German). Of course, a phonetic dictionary is still needed to recognise the individual words.

Most speech recognition systems improve over time based on user feedback. Early versions of Dragon Naturally Speaking software are an example of this type of speech recognition. This can be used to automatically transcribe texts.

Language models and statistical analysis

Recognising speech is even more complex than identifying phonemes and matching them with stored data. Why is that? If you've already forgotten, scroll back up and read the four points under the title "Listening to and analysing speech".

Variable speech, pronunciation, homophones and misunderstandings cause many errors in speech recognition systems that are based solely on pattern and feature recognition. This is where language models can help.

Language does not simply consist of randomly strung together sounds. Spoken words refer to the words that come before or after them. Language is context-dependent. For example, a personal pronoun is followed by a verb, i.e. "I am" or "you have" or "we want". And adjectives come before nouns.

If the speech recognition system now attempts to understand spoken language and recognises the example sentence "You have a ******* car.", the recognition system can assume that the missing word is an adjective. If at least one phoneme of the word has been recognised, speech recognition has another clue.

More or less all modern speech recognition systems use language models and statistical analysis at least to some extent. They include probabilities of which phonemes follow others or the probability of which words follow others. Based on this data, a so-called "hidden Markov model" is created.

Artificial neural network

Hidden Markov models have been used in speech recognition since the 1970s. They work very reliably. However, our brain does not use Hidden Markov Models for speech recognition. This works via dense layers of brain cells that process information that comes in via the cochleae (cochlea).

In the 1980s, scientists therefore developed computer models that mimicked how our brain recognises patterns. However, due to the effectiveness of Hidden Markov Models, this approach remained a side effect for some time. In recent years, however, scientists have begun to combine artificial neural networks with the Hidden Markov Model. This can further increase the probability of better understanding of speech recognition.

Hidden Markov models and artificial neural networks are used today under the buzzword "deep learning". I will be writing an article about this in the near future. So for now, I'll leave it at the absolute basics.

The age of intelligent assistants?

Digital assistants such as Siri, Cortana etc. do more than just understand speech these days. Thanks to natural language processing, they also understand the meaning of what is being said. This means that what is said also has real consequences. For example, if I ask about the weather, I actually receive information about it. But it goes even further, as the video below shows.

Does this mean that in future we will only talk to computers instead of giving them commands via a keyboard? As you read above, Hidden Markov Models have been standard in speech recognition since the 1970s. Reasonably reliable dictation software has been around since the 1990s. Despite this, I personally see very few people speaking with their computer or smartphone.

Why is that? We humans have not unintentionally devised multiple ways of communicating. Oral language is direct and blunt. If, on the other hand, we want to express deeper thoughts, writing is the way to go. But this is not the only reason why writing is a more intimate process than speaking. When we write, our thoughts are initially only for us. When we speak, everyone can listen in.

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all