Background information

Working 450 metres below the surface

by Simon Balissat

They’re the guardians of the underworld. 30 men of the sewage network maintenance take care of 300 kilometres of waste water canals. When the inhabitants of the country’s capital have done their business, their work begins.

The first breath I draw feels like a rotting dishcloth enveloping my lungs. It’s morning. While the people of Bern are starting their day with showers, breakfasts and foaming milk for their second cup of cappuccino, the air is thick underground. A worker clad in a rubber suit dips his five-metre high-pressure lance into the sewage basin – quite literally stirring sh*t. Next to him, a greyish-brown waterfall from the Northern municipalities gushes into the Seftau pumping station. The iron rungs leading up the concrete wall to the shiny wet ceiling are covered in toilet paper for many metres above his head. Silent proof that we haven’t seen anything yet. Welcome to the underground – connected to every drain and just a flush away.

Rewind a good hour. Raphael Flückiger and Alain Fallegger are sitting in the canteen, talking about their underground empire over a cup of coffee. Flückiger manages the sewage maintenance company and its 30 employees. Fallegger is his deputy for all things maintenance. The air is filled with the scent of freshly ground coffee beans. Their stories are easy to digest in theory and I learn that rain is referred to as an event. They tell me that these «rain events» are harder to predict than people’s daily toilet business but are still very much part of the business. The Bernese sewage is a combined sewer system. Rain and waste water flow together towards the treatment plant that can purify up to 3,000 litres per second.

«These days, the river Aare is considered almost too clean,» Flückiger says. «Before the treatment plant was put into operation in 1967, the river was too dirty to swim in.» The men weigh up the pros and cons of separate and combined sewer systems. On the one hand, the treatment plant shouldn’t be flooded with clean water but should clean waste water. That’s an advantage of a separate system. «On the other hand, street water, or run-off, is also toxic,» Fallegger argues. What this first rain, or first flush, drives into the sewers after a dry spell is also questionable. «I’d choose faeces over toxic run off.»

And so the layman learns: there’s a lot more to this than you’d think. It’s a dirty business that requires lots of know-how and infrastructure. This is a story about sewers, rainwater overflow basins, manholes, throttle regulators and flow regulation systems. From expertise to excrement. This is about a system of urban drainage that has grown since the Middle Ages. If you want, it can all be explained with unwieldy technical terms. Or you can simply experience it first hand.

Civilian life is handed over in the changing room. The next door is where the «dark zone» begins. Venture beyond it and you need to be clad in workwear and follow safety instructions. Anyone entering the sewer system needs to be prepared and well equipped. Reflective gear, helmet and lamp. Gloves, of course. And thigh-high rubber boots with spikes. Things can get slippery, after all.

An industrial climbing harness. The shafts can be very deep. Then you get a gas detector – many dangers down here are invisible. «This one here measures oxygen levels on the one hand and explosive substances, such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulphide, on the other,» says Raphael Flückiger and shows me the small device that sounds an alarm as soon as levels reach a critical level. Carbon monoxide in the exhaust fumes emitted from the cars above could sink down into the sewer. It’s toxic even when it’s not combusted. Petrol is also bad for your health. And those are just two of many potential dangers.

«Obviously, digester gases occur frequently,» Raphael Flückiger explains. «The device is a type of life insurance that tells you when you’re in a danger zone.» In a case of emergency, you’d reach for your «Oxyboks» – a small black box that looks like a binocular case. You attach it to your belt and carry it on your hip. «The Oxyboks contains granules that oxygenate exhaled air for up to 25 minutes.» A truly life-saving device if the danger is airborne. If you’re surprised by water, however, it’s useless.

«Every morning, we receive a detailed weather report tailored for Bern. In addition, we all receive alarm text messages on our mobiles as soon as a rain cell develops,» Flückiger adds. «The shaft guards would be able to receive the message and warn their colleagues in the shaft by Morse code or loud whistling.» Nobody goes down here alone.

Firemen have been known to stress out during our rescue exercises.

Once your lungs get used to the stuffy air and the roar of the water stops ringing in your head, the small rainwater overflow basin in Seftau is not even that unpleasant. A perfect lecture hall for sewer novices. An unassuming, easily accessible brick building. The plant was renovated four years ago and is now at the cutting edge of technology. We leave our boots and climbing harnesses in the car and step onto the balcony that gives us a free view of the goings-on. The lower part of the basin is almost five metres deep and scarcely filled on this Monday morning. At the very bottom, a pump is transporting the waste water to the other side of the river Aare. «This basin is deeper than the collector sewer duct that channels the water to the treatment plant,» Flückiger explains.

To ensure that the pump works efficiently and no solids settle, the man with the lance whirls up the remaining water. The walls are also cleaned regularly. Further up, three pumps are waiting for heavy rainfall, which can push the basin to its capacity limits. «If too much water were to accumulate, we would have to relieve the system by discharging diluted waste water into the Aare,» says Flückiger.

The system comprises 115 relief points. The large quantities of water are pumped, collected and managed. At times, this requires quite a bit of energy, like here at the rainwater basin. The Office of Engineering, which is in charge of sewage network maintenance, runs 24 of these stations. In other places, the sheer force of the water needs to be slowed down and energy reduced. This is what happens in vortex drop shafts. The shafts send the water down a huge spiral slide. The whole system is designed to balance things out. «The rainwater overflow basin holds back the water and activates a controlled transfer as soon as the treatment plant has free capacity,» Flückiger half shouts, competing against the constant growl of the waste water.

In 2020, it’s not just waste water and rain run-off that’s flowing, but also streams of data containing information about the state of the systems in the sewage. «2,500 data points send updates every 15 seconds,» explains Alain Fallegger. And if a pump’s performance isn’t right, the reason could well be as plain as it is annoying.

Dental floss and indecomposable wet wipes are our declared enemies. They clog up the pumps.

Back in the fresh winter air, the day exudes lightness. The morning sun is reflecting off the surrounding rooftops, the water of the Aare is gently flowing downstream and the waste water underneath it forgotten as soon as the door to the pump station is closed behind me. «We swim here in summer,» Flückiger says before he gets into his car and is confronted with a small problem.

«There’s a huge hole below this car park,» the trained civil engineer assures me. But that’s not the problem. The hole is the throttle regulator and flow regulation site Wylerbad belonging to the collection sewer Wankdorf-Aare, which is currently being renovated. It’s a massive construction, deep under the surface and one-and-a-half kilometres long. The storage system can handle up to 6,000 cubic metres of water. That’s six million litres. More than two brimful Olympic swimming pools. And yet that’s only a fraction of the hundred million litres that flow through the sewage network every day. The site fence surrounding it is definitely a good idea. However, we’re missing a key.

While Fallegger tries to organise one, there’s time for a few anecdotes. I learn about searches for wet wipe sinners with hooks and bait. About flushed bikinis or failed toilet burials for pets. Anything that can be squeezed down the drain will be.

Occasionally, things end up in the sewage that their owners desperately want back. The sewage network maintenance team even offers free help for those unlucky individuals who accidentally drop their keys or mobile through the gutter grates. «We prefer to offer that kind of service than have people poking around, trying to get to their things on their own accord,» says Flückiger. And a lost key really is a pain. Thankfully, the one we need has arrived. The one for the site fence. With a few flicks of the wrist, Flückiger and Fallegger first open the lock and then the underground. The parking spaces give way to a silent abyss.

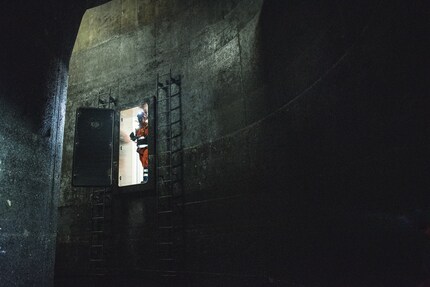

There’s no roaring, no noise rising up. The sewer was switched off for renovations in December. «The waste water is currently discharged through the old system above. This can only be done between late October and late March,» says Alain Fallegger, who’s the first to secure himself with a snap hook and climb down in the gleam of neon lamps. «If there’s heavy rainfall, the system above is not enough.» A long ladder leads us into the abyss. Heart rates rise and steps echo in the darkness as we descend deeper and deeper into the shaft.

We pass the overflow rim to which the water can rise. It’s hard to imagine, looking at how dry and clean the shaft is. «We’ve cleaned everything for the master builder,» says Fallegger. «Otherwise you’re looking at an accumulation of mud and faeces.» Eight cubic metres of sand, gravel and rubble had to be removed from the shaft, which is now home to just a trickle. The shaft is a gaping hole – the helmet lamps illuminating only a few metres of it. It’s an echo chamber, reflecting our voices, while Fallegger takes the lead and explains: «You can cross the entire city like this. From the Allmend all the way to the ice stadium.»

Darkness increasingly engulfs us with every step we take. The large illuminated shaft turns into a tiny light at the end of the tunnel. For decades, the water, and everything it contains, has been eating away at the structure. Or is stuck to it. «That’s sewer film,» says Fallegger, as he picks off a few dried up particles from the ceiling that fall to the floor like sad confetti. The sewer film is a bio film that covers the entire pipe. «Normally, it’s slimy,» he explains in the echo of his own words.

«The draught in the dry sewer has made it papery. It needs to be removed before the renovation.» If it’s mixed with mortar, you’ve got a problem. Sewers have a lifespan of 80 to 100 years. So renovation should definitely be done properly. The bed of this collection sewer is washed out and rough. You can just about make out coarse pebbles. «The bed should be smooth,» says Fallegger. Otherwise, the gradient of about one percent in this sewer is practically perfect. In spring it will be ready again to carry, store and transport water in a controlled manner. It will overflow once or twice. First, this will happen at the other end, one-and-a-half kilometres further down. This is where the overflow rim is lower and a rake sieve catches the coarsest dirt. «We aim to retain floating solids including cotton buds, condoms and toilet paper,» says Fallegger. «If more water keeps on spilling into the sewer, we provide emergency relief on our side.»

The unfiltered water then discharges into the Aare via the higher overflow rim. «It’s quite possible that there are twenty cases a year in which we need to provide relief,» Fallegger estimates. Depending on the storm season. Even down here, it’s hard to guess how diluted the waste water is. Nonetheless, thoughts start accumulating like sewer film on concrete. Discharge into the Aare? The treatment plant only introduced in 1967? Experts in the field would laugh at my astonishment. In Brussels, the capital of the EU, unfiltered waste water was flowing into the Zenne and further into the North Sea until 2007. Milan, a city with over a million inhabitants, only introduced a treatment plant in this millennium. And many large cities are still a long way away from introducing one.

No water drainage system is perfect. They grow over centuries and must always function. Here in Bern, money is pumped into the maintenance and development of the underground system. The infrastructure is worth around one billion francs. About ten million are expected to flow into the annual upkeep. Something is flowing alright. A threatening roar penetrates the dark tunnel, triggering primal fears. Is this a high tide? «About 800 metres further up, someone’s using a lance,» Fallegger reassures me. There’s work to do everywhere and 75 kilometres of the sewer system are walkable. Having said that, «walkable» is not entirely true. The place where Stefan Botta’s hard at work brings you to your knees.

Under Bubenbergplatz, close to the train station, the luxury of a drained and cleaned sewer is soon forgotten. «This is the Insel sewer,» says Alain Fallegger. «It’s attached to the Insel Hospital and the digitec shop.» He descends into the cellar, passes a yoga room and a martial arts studio. Time for some full contact with reality. Boots: check. Face mask: check. «Oxyboks»: check. We’re going to need the full outfit now. In the next corridor, tucked away between stacked beer benches, there’s an open entrance. Underneath, the muddy brew is rolling by in slow motion.

Excrement, tangerine peels, a condom. It’s hard to ignore all the detail; it’s impossible to stand up straight. A ceiling height of 1,20 metres forces you to lower your gaze. The climate is cavelike, humid and warm. My sense of smell is rebelling, the walls are close and oppressive, but at least they give your hands something to hold on to. We stagger along the waste water flow. Stepping in and out of the water, the light cones of our helmet lamps leading the way. Until we reach a makeshift wooden dam with a plastic pipe leading through it. A small sewer inside a sewer. Stefan Botta is kneeling next to it.

You can’t shrink back from walls that are alive.

The group leader and two of his colleagues are renewing a connection. Daily business. It will be done in three days. «Lately, we’ve been working on smallish construction sites where we do a lot of the work ourselves,» he says. Other jobs are outsourced. 30 men in charge of 300 kilometres of sewage maintenance – there’s no way they could manage. The sewers are considered walkable up to a height of one metre. From this point of view, things could be worse. Botta is relaxed. He fills up with concrete, plasters and sits in the stench of the waste water without being able to stand up straight. This is a job that’s not easy to stomach.

«There are cockroaches, mice, rats,» he says with a grin. Botta is just as laid-back about the critters as he is about gross greetings from above. «This is where you find pretty much everything that shouldn’t be down here,» he tells me. «From women’s stuff to cutlery to toys.» It’s been almost three years since Botta joined «the sewage». Depending on the job, he and his colleagues spend up to five hours at a time crouching or bent over in the stuffy underground. This kind of work requires careful planning, stamina and teamwork. «We’re a great gang; things generally run smoothly and everyone uses their brains,» says Botta. «It’s fun, working here.» A remarkable sentence considering the fact that this is the place of nightmares for many others. The only ones working in an even more confined space than Botta are robots.

What is carefully hoisted into the sewer on Bümplitzstrasse by means of 600 metres of cable is reminiscent of a moon rover. The 60,000-franc vehicle is equipped with a swivelling camera, bright headlights and small black wheels. It’s all set to discover the strange world below. This was last done by its predecessor around ten years ago. «On average, we cover about 30 kilometres per year,» says Michael Mitter, as he positions his valuable assistant and utters a curse that wasn’t intended for the robot. «Goddamn pipe!» he exclaims. «We should’ve used those other wheels, Theo.»

His colleague, Theo Maibach, is sitting in the van today and in charge of steering the robot vehicle. The two of them are a well-rehearsed team, always out and about together. They document the state of the sewage system and note down every connection, every tear, every pipe collar. Plastic pipes like this one here are a problem. «Not our favourite material,» Mitter says. «It’s slippery, that’s why we have granule-coated wheels.» There are plenty of accessories stored in the back of their van.

Suspended, egg-shaped driving aids that provide lateral support in oval sewers that taper towards the bottom. Extra weights for more traction. An additional camera module that can be sent out up to 30 metres to explore lateral pipes. The possibilities are practically endless. Nevertheless, there’s always the risk of the robot getting stuck. «Let’s say threads wrap around the axles. There’s no way we’ll manage to drag this baby out again,» says Mitter, who's been with sewer TV for 17 years and is a landscape gardener by trade. In his current job, the only plants he sees are roots growing through sewer walls. That’s when things need to be renewed.

Theo Maibach is looking at five monitors and steering the robot with a joystick. «Lateral connection closed,» he enters into a chart and repositions the camera. «We always take a long shot as well as close-ups,» he explains. Together with Michael Mitter, he assesses how far the expensive piece of equipment can be pushed in terms of manoeuvres.

Their video footage, packed with data and coordinates, is invaluable for their colleagues from the planning department, where decisions are made about renovation measures that need to be taken. The footage is also important for people like Stefan Botta. It allows him to get an idea of what to expect down in the sewer before he goes to work.

«There’s a nugget down there,» says Theo Maibach with a grin and pans the camera to a little brown obstacle. Mitter and Maibach advance all the way to the sewer system’s capillaries, from which the water should be flowing freely into the underlying veins – the collector sewers. A cushy job compared to those who need to go down there.

Strictly speaking, this door is a window. Below it: nothing. A ladder leading to the collection sewer Länggasse-Aare is mounted to the wall right next to it. These walls are alive. Everything’s covered in sewer film and the waste water current is huge.

Careful steps in the sludge, one hand on the safety rope, toilet paper everywhere. There’s no time to be repulsed. «It’s just stuff, I can handle that,» says Martin Pauli, a sewer veteran, who had his «sewer baptism» ages ago. It involved slipping, plunging, changing, continuing. An occupational hazard. Fortunately, he got off lightly. «Here, the current would’ve been too strong. You’d be swept away,» he warns me. I keep that in mind, hold on tight and tread carefully.

His colleague, Markus Neuenschwander, opens one last sewer port. This interspace has not been fully pumped dry and reminds me of a sinking submarine. The water’s knee-deep until Neuenschwander releases the bar of the next heavy door, pushes it open and triggers a suction. Undefinable things brush past my rubber boots as the waste water pours into the next big sewer. Each item washing around my feet a piece of evidence that everything’s still here. Excrement, used tampons, shower water and all that liquid waste we send down the tubes every day. None of it simply disappears when you flush it. All it does is go underground, disappear from people’s view and consciousness. And that’s only because things no longer stink to high heaven as they did in medieval times. And that’s thanks to the invisibles in reflective gear. The indispensables of the underground.

Simple writer and dad of two who likes to be on the move, wading through everyday family life. Juggling several balls, I'll occasionally drop one. It could be a ball, or a remark. Or both.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all