Background information

Are you sitting on a gold mine? Valuable collector’s items from the nursery

by Michael Restin

Maps should help you find your way, not confuse you. Nevertheless, there are an increasing number of streets and even whole places on maps that you will never find in real life. This is no accident.

Recently, I rented a car for the holidays, choosing to do without a conventional sat nav. Partly because the extra costs (which wouldn’t have made any difference) annoyed me and partly because I somewhat arrogantly thought that I didn't need a brightly lit device on the dashboard that would single me out as a tourist from a mile away. Google Maps on my phone should work just as well.

It did actually work relatively well. I made a few mistakes here and there and there was a bit of hassle placing my smartphone in the car, but I always got where I needed to go. For short distances, I tried to memorise the route beforehand: after the BP petrol station, there are three streets that branch off to the left, and I need to take the fourth. Very simple, actually.

Apart from the fact that a small cul-de-sac showing up on Google Maps didn’t exist on the real road network. Since I reached my destination anyway, I didn't pay much attention to the error. Until I stumbled across the term trap street on the internet.

Trap Street isn’t a new song from the hip-hop subgenre of the same name; it’s the term for deliberately incorrect streets on graphic maps or in digital geodata. Huh? Shouldn’t maps guide us rather than disorient us? Yes, that’s why trap streets are actually always dead ends or secluded walkways.

They’re not intended to target us consumers, but ward off intellectual property theft. Maps are protected by copyright and the copyright belongs to the cartographers. As maps and geodata are ideally always identical, it’s difficult to prove that your cartography work has been plagiarised, unless you deliberately add small errors that make the map unique without harming the user. If the map or digital geodata is copied illegally, the trap streets are also transmitted and the culprit is caught.

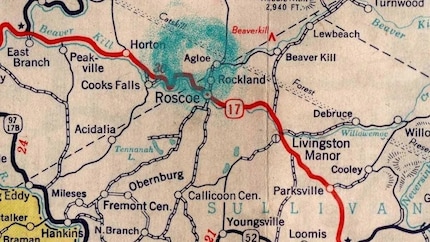

But there’s one example where this didn’t quite work. Not an invented street, but an entire place – what’s known as a paper town. In 1925, cartographer Otto G. Lindberg and his assistant Ernest Alpers set about creating a street map of the state of New York. To protect their copyright, they added in Agloe – an anagram of the first letters of their names – at the crossroads of two country lanes. When the Rand McNally company also published a map of New York a few years later and the town of Agloe was on it, Lindberg and Alpers were sure that the map data had been stolen from them.

However, Rand McNally’s attorneys assured them the place was real, which was true. In the 1930s, an Irish emigrant opened «Agloe Fishing Lodge» there, presumably because he had seen the name on the Lindberg and Alpers map, as they were free at many gas stations at the time. The name then took root over the next few years with the opening of a small shop and a mention in a New York Times travelogue. Meanwhile, Agloe has disappeared once again.

There are few other examples of trap streets and paper towns, as cartographers understandably keep a low profile. It was only in 2005 that a spokesperson for the «Geographer’s AZ Street Atlas Company» confirmed to the BBC that there were at least 100 fictitious streets on their London map. The Greek road atlas of Athens is one of the few examples in which thieves are explicitly warned that the maps include false roads.

Incidentally, the Swiss Federal Office of Topography (swisstopo) doesn’t participate in this practice. Its maps contain neither trap streets nor paper towns. They’re realistic, as communications specialist Sandrine Klötzli assures me: «Our data was always correct and still is today.» As of 1 March 2021, swisstopo’s digital geodata can be used (even for business use), redistributed and reprocessed free of charge, provided that the source is referenced.

Maps are not only distorted as a plagiarism trap, but also for military reasons. Either to make it more difficult for terrorists to plan attacks – which is why certain government buildings and military facilities are hidden on Google Maps – or to keep the upper hand in the event of war. The commanders of the former Soviet Union were particularly good at putting enemies on the wrong track. During World War II, they deliberately gave the German military fake maps that led to deserted swampland, and they used the same methods to control their own citizens in the GDR (article in German). Those who wanted to flee to the West with a public map had little chance of success because the borders were incorrect.

Even the data on my nemesis, the built-in sat nav, is not safe from manipulation. The «Global Positioning System» (GPS) is operated by the US Department of Defense and was originally reserved for military use. However, anyone has been able to receive the satellite signals since 1983. There were serious concerns about misuse, so the signals were artificially degraded for the general public («Selective Availability») and precise position determination was only possible to within 100 metres. In 2000, US President Bill Clinton overturned «Selective Availability», but the US government could reactivate it at any time. For this reason, the EU has developed its own and the first civilian satellite navigation system, «Galileo». However, most sat navs still use GPS data – either exclusively or alongside other systems.

Despite the remote risk of suddenly only being able to get within 100 metres of my destination, I will use a built-in sat nav for my next holiday. It doesn’t go into sleep mode, nor is it dependent on mobile data. Also, I can see its display properly, as opposed to the phone screen that’s somewhere in the centre console.

My life in a nutshell? On a quest to broaden my horizon. I love discovering and learning new skills and I see a chance to experience something new in everything – be it travelling, reading, cooking, movies or DIY.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Michael Restin