Which is better: RAW or JPEG?

Cameras save image files either as JPEG or as raw data. Opinions differ widely as to which is better for whom. Here you can find out not only the theory, but also the practical application.

If you're interested in photography, you've probably heard of the RAW format. You probably even know roughly what it is. The RAW format is a topic that comes up from time to time, recently even in the smartphone sector.

What exactly RAW is and what it does is relatively easy to understand in theory. However, it is much more difficult to decide for yourself whether you want to shoot in RAW or JPEG. Both have their advantages and disadvantages, and what you prioritise and to what extent varies greatly from person to person. In this article, I want to help you decide.

Almost everyone can do RAW

The days when RAW was reserved for the more expensive cameras are long gone. Our shop currently lists almost 300 cameras that support RAW. You only need to take a closer look at the compact cameras. Some of the cheaper ones can only do JPEG.

This is currently the cheapest camera with RAW support:

This is the smallest:

And this is the hardest:

You can see whether your camera can handle RAW by going to the image quality menu. In addition to various JPEG sizes and quality levels, RAW should also be listed there.

RAW in four sentences

Most cameras today can save photos not only as JPEGs, but also in their own format (called RAW or raw data format). This is not a standardised file format, but varies from camera to camera. Consequently, each manufacturer also uses its own file extensions, such as CR2 (Canon), NEF (Nikon), RAF (Fujifilm), ORF (Olympus) or ARW (Sony). These files are larger than JPEGs because they contain much more colour information.

The theory: what is better with RAW

Specifically, RAW files store more brightness gradations per colour channel than JPEG files. In a digital photo, each pixel has a specific colour, which is made up of three brightness values of the colours red, green and blue (RGB colour scheme). Pure white, for example, has the maximum brightness value from all three colour channels, pure red only from the first and nothing from the other two. In RAW format, more intermediate levels can be saved in terms of both brightness and colour tone.

A JPEG has 256 gradations (8 bit) per colour channel. The fact that there are three colour channels (red, green and blue) means that 256 x 256 x 256 different colours can be displayed, i.e. 16.7 million in total.

In RAW, there are 4096 (12 bit) or 16384 (14 bit) gradations per channel, which results in a total of 68.7 billion or even 4.4 trillion colour combinations.

However, this is only relevant for editing, not for the final result. Firstly, most PC screens cannot display more than 16.7 million colours. Secondly, the human eye cannot distinguish many more colours. And thirdly, RAW processing ultimately results in a JPEG. The end result is always JPEG, whether you shoot with RAW or not. The only question is whether you want to leave it up to the camera to turn the image into a JPEG or whether you want to do it yourself.

The practice: RAW vs. JPEG post-processing

The additional colour gradations therefore provide an advantage in post-processing. But how does this actually work? I will demonstrate this with the following example:

This image shows an extreme contrast: the flame is very bright, most of the rest is very dark. Dark colour tones can be selectively brightened in any reasonably usable image editing tool, i.e. without the lighter parts also becoming lighter. This works with both JPEG and RAW, but with RAW you have more leeway. Here, however, the transition from light to dark is so harsh that the brighten function hardly changes anything. But extreme cases like this are the best way to demonstrate the difference between RAW and JPEG in editing.

You can see in both images that the area around the flame has been lightened. However, while the colour gradient from light to dark is reasonably smooth in the RAW image on the left, you can see clear colour gradations in the JPEG on the right. This effect is called "colour banding".

Darkening photos that are too bright is similar. The only difference is that brightening generally causes fewer problems, both in RAW and in JPEG. Even supposedly black parts of the image are rarely completely black, as there is still information present. With white image parts, on the other hand, it is often the case that they are completely white. This means that the information is lost and can no longer be retrieved. However, this happens faster and over a larger area with JPEGs than with RAW files.

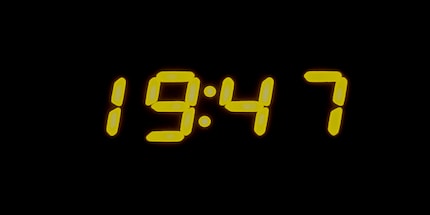

The clock is overexposed: The numbers should be yellow, not white, and the surroundings should be dark, not yellow.

In RAW, I get this pretty well in post-processing:

In JPEG, on the other hand, I can forget that. In the white parts of the image, the image information is actually lost because it was saved as pure white due to insufficient colour gradations.

JPEG go home? No, it's not that simple

In the above comparisons, JPEG comes out pretty flat. But in honour of JPEG, I have to say the following:

- I have deliberately chosen extreme examples here to demonstrate the effect as clearly as possible. With the vast majority of photos, the effect is not nearly as blatant. To be honest, it took me several attempts to find an example photo that would make the differences immediately visible to everyone.

- RAW flexes its muscles, especially with high contrasts. Most cameras have one or more mechanisms in JPEG mode to cope better with high contrasts. One of these is the adjustment of the gradation curve during shooting. At Nikon, for example, this is called Active D-Lighting, but each manufacturer has its own names. Another method is fully automatic bracketing: the camera takes the same image several times in succession with different exposures and then combines the individual images to create an HDR.

- RAW also has disadvantages. We'll come to that now.

The disadvantages of the RAW format

Processing is not optional. RAW files must be "developed": They must be opened by a RAW converter and converted into a JPEG. This point is often underestimated in the initial general enthusiasm. RAW converters can also develop images in a batch process according to a standard specification and export them as a JPEG, so that you don't have to process each individual image manually. However, this does not utilise the full potential of RAW. Therefore, if you shoot in RAW, you have to post-process every single photo. Each image must be sharpened to a greater or lesser extent, brightened, white balance adjusted and contrast enhanced. The end result is still a JPEG. And this will only really be better if you have enough knowledge and experience in post-processing.

Software lock-in. If you edit a RAW photo in a RAW converter such as Lightroom and do not export it as a JPEG, you will only see the result in this very RAW converter. The embedded JPEG will not be updated. Worse still, if you switch from Lightroom to another converter, for example, it won't apply your hundreds or thousands of edits. This is because every converter works differently and there is no standardised procedure for how this information is stored and interpreted. The processing information is not saved in the RAW file, but in an additional file with the extension .xmp.

I also mentioned the last point because the topic of "should I move away from Lightroom?" is currently topical.

Compatibility. RAW files cannot be opened by most programmes. As every camera has its own RAW format, RAW converters must always be updated, otherwise the images will no longer be recognised by new cameras. It often looks as if RAW files can be viewed with a simple image viewer. But this impression is deceptive: what you see there is a JPEG that has been embedded in the RAW file. The raw data itself must first be interpreted by a RAW converter before you can view the image. This is why the same RAW file looks different in every RAW converter.

File size RAW files are much larger than JPEGs. Whether this is really a disadvantage depends on your equipment. There is usually enough space on the hard drive, and perhaps also on the SD card. It can be more of a problem to save the huge files to the card quickly enough, especially when taking fast continuous shots. The camera usually shoots the RAW images quickly until the buffer is full, after which the speed drops. Some cameras have a large enough buffer to maintain high RAW continuous shooting speeds for several seconds.

Uniform colouring - even in RAW

When you shoot your images as JPEGs, the camera converts the raw data into the final format. It does this using a specific process developed by the camera manufacturer (known as the JPEG engine), which is why the colouring differs slightly from brand to brand.

More important than the camera brand, however, are the image settings. Most cameras have various image styles to choose from: natural, vivid, pop, pale, etc. In addition to the colour balance and saturation, the sharpness can usually also be adjusted. Somewhere in the camera settings, you can also specify whether and to what extent the camera should suppress image noise. Too much image noise can lead to watercolour-like blurred images.

As long as you always use the same image style, the colouring of the JPEGs will remain reasonably consistent. When developing a RAW image manually, on the other hand, there is a risk that each image will be optimised on its own. Then it may look good on its own, but the colour does not match the rest of the series. This can be a problem with photo books, for example.

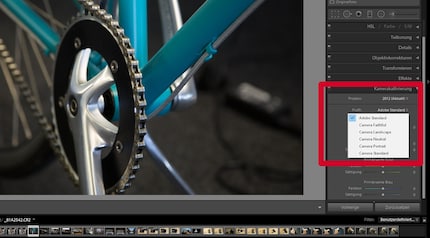

But that doesn't have to be the case, because you can also use the camera's image styles in RAW format. However, this only happens afterwards on the PC, whereas it is "fixed" directly in the image file when shooting in JPEG. In Lightroom, for example, go to Develop and then to the "Camera calibration" section. In addition to the Adobe default settings, you will also find various image styles that correspond to those of the camera.

You can see whether such image styles are stored for your camera in Lightroom in the directory

Programmes\Adobe\Adobe Lightroom\Resources\CameraProfiles\Camera

What to do?

Now that you know the pros and cons, you can better decide which file format you want to use. However, this article alone is not enough to really make the right decision. Only experience will show you which advantages and disadvantages are important to you.

A good way out for those who are undecided: Many cameras can save RAW and JPEG at the same time. RAW only brings added value with a certain amount of experience in image processing, and you also need to be prepared to invest the necessary time. If you think that this might be an option for you later on, but not now, save the RAW files just in case - hard disc space costs nothing. And in the meantime, use the JPEGs.

And then there's also DNG

In addition to RAW and JPEG, there is a third option: DNG. The abbreviation stands for Digital Negative. Adobe invented this file format and published the specifications. DNG can store just as much colour information as RAW, but is a standardised format that can be read by all RAW converters and some other photo applications. Adobe offers a free DNG converter with which you can convert all RAW files to DNG.

Even with DNG, however, different RAW converters are not compatible with each other. This has nothing to do with the file format, but with the fact that the processing works differently in each software.

DNG may not save all of the metadata contained in the RAW file. Otherwise, there are no disadvantages compared to RAW.

Unfortunately, hardly any cameras use the DNG format because every manufacturer does its own thing. But for some time now, there have been smartphones that save photos directly in DNG. In the future, many models will probably be able to do this, as iOS and Android already have everything they need for this.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all