Background information

Garmin, Fitbit and all the rest: how smart is your smartwatch? An expert explains in this interview

by Patrick Bardelli

Everyone wants to get their hands on our data. And social media platforms such as Facebook and TikTok are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the data race. How can we win when there’s not a level playing field? ETH Zurich’s Hönggerberg campus has the answer.

You’ve been an online shopper from the start. And you’ve had a Facebook and Instagram account for years. You’re into sports and you use a wearable device to track your activities. You also track your eating and sleeping habits. When you shop offline, you swipe your Cumulus card at the checkout. So nice of you to hand over all your data like that. This is in keeping with the news that Google is buying Fitbit for 2.1 billion dollars.

My data, your data, our data. Who does all this data belong to and what are people doing with it? Ernst Hafen is a Doctor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and Professor at ETH Zurich. He has a radical answer to this question: «Our data belongs to us and we’re giving it away freely for research purposes. I’m not just talking about data collected by Facebook and the likes. I also mean our decoded genome.»

We’re in competition with the market-driven surveillance capitalism of the US and the state-controlled model in China.

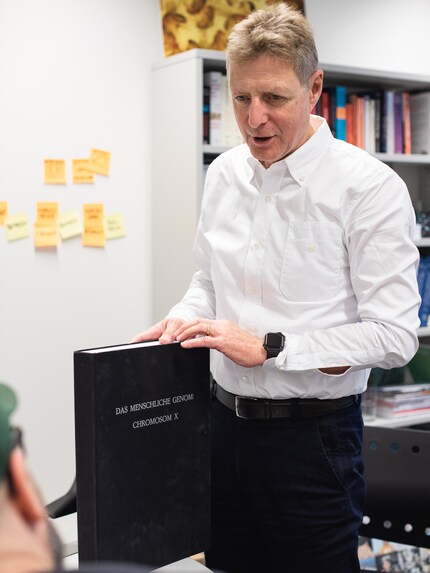

Ernst shows me a book when I visit him at ETH. It’s a great wedge of a tome with the title «Das menschliche Genom: Chromosom X» (The human genome: chromosome X). The human genome is made up of six billion letters. Our double helix comprises three billion rungs or letters from our father and the same amount from our mother. The human formula was decoded 12 years ago. This book lists 154 million letters from a male chromosome. If you were to print all six billion letters, you’d need 46 books: 23 for the letters from the mother and 23 for those from the father.

This information can be found in each individual cell: in each skin cell, in each intestinal cell, in each nerve cell and so on. And each time one of these cells splits, our body writes these 46 books again, as error-free as possible.

6,000,000,000 letters is a lot of data

Biologist Ernst Hafen: Yes, it’s a lot. Initially there was interest in printing the whole genome in a book but then they just printed one chromosome.

**Certain rows of letters are in bold in the book. Why is that and what does it mean?**

Those are our genes. The building blocks for the protein in our body. In total, the human body is made up of 25,000 genes.

**But only a few lines are in bold. What about the rest?**

We still don’t know. It’s something that’s bound to keep researchers busy for the next few decades.

**Is our genome really decoded?**

My genome has been decoded and so has that of my three sons and my wife. Decoding your own genome has been possible for the last 12 years. In the US there are companies that specialise in this practice. One of them is called 23andme, which is a Google spin-off. They sample about one million of the six billion letters. It used to cost 400 dollars but now it’s just 100. However, complete decoding would have set you back 100 million Swiss francs back in the day. Today you can get it for 1,000 francs.

**Hold on a moment. Are you telling me your family’s decoded genome is in the hands of Google?**

Yes, that’s correct. But you see, I’m a biologist. And the opportunities this opens up for me as a citizen rather than a professor at ETH are fascinating. It makes me a kind of «citizen scientist» and lets me contribute to research in an invaluable way with my genome data. But we still have a long way to go.

**What do you mean?**

23andme handles my data and that of my family. That’s fine – it’s their business model. But when it comes down to it, it’s rather unfair that we have to give away our fitness, sleep or even genome data to someone in return for a free service in the form of an app or social media platform. Wouldn’t it make more sense to do something more sensible with our data?

**Such as?**

We still don’t really understand how diet affects this. You can write off pretty much all the studies on diet because the connection between food and health is so complex and unique that there’s no universal answer. We need millions of pieces of data from individuals that contribute actively to medical research. However, there is very little – if any – access to data from hospitals or doctors’ practices. And we normally don’t have access to the majority of the remaining data, such as health data from countless smartphones and wearables. But this is the type of data that would be immensely interesting for research or hospital use.

Let me give you another example. Imagine you’ve had a hip replacement. You use the app from the clinic where you had your operation to record your recovery, including how many steps you walk each day and any health problems you encounter. The clinic then has access to all this data. This lets them create something called a «patient reported outcome», which is extremely valuable for the whole health system.

**That’s all well and good but what benefit do I get from sharing my data?**

Good question. This leads us to the three main characteristics of data. Firstly, they can be copied. On top of that, we’re all data billionaires, whether we live in Switzerland or in Tanzania. We all have a similarly large amount of personal data. And thirdly, we can become the biggest data collectors. Google and Galaxus might know a lot about me but not everything by a long shot. You would know the most about yourself if you could merge all your data. By that I mean, do you have all your data from Google, your Cumulus card, your wearables and all the other businesses that track you?

**You might have some of that data. But not all of it combined.**

But you can see that pulling all this data together would make sense. Imagine it like a bank account, a place where you store all of your assets. If you have any questions about the third pillar, you go to the bank and pay to speak to an advisor. That’s exactly how the data service sphere will work in future. For instance, a start-up could develop a diet plan based on your Cumulus data combined with genome data and your blood levels.

**Is this your business model once you retire as a professor at ETH?**

It’s already my business model, if you want to call it that. But I don’t trade people’s data. There are already platforms that do that. Data ends up being sold to the highest bidder. However, I don’t think capitalism works in this instance. In the US, you get 70 dollars for giving blood. That just means you only get people going who need the money. That’s not the way to do it.

**You’re president of the board of directors for Midata cooperative.**

That’s correct. Midata was developed in 2015 as a nonprofit organisation in cooperation with ETH Zurich and Bern University of Applied Sciences. The aim was to highlight the way data can be used for the common good and simultaneously meet people’s demands of keeping control of their own personal data.

**How does that work exactly?**

Personal data gets stored on the data platforms at Midata. Account holders can take part in app-based research projects and use app-based services. All data sets are encrypted, which means that only individual account holders have access to their data. Data access is always logged. To facilitate global research and clinical studies, we set up secure data access via various national cooperatives. This ensures account holders always have control over their data.

**Without any financial ulterior motives?**

On the contrary. It’s not about making a large profit from your data as quickly as possible. Take the pharma industry, for instance. The cost and effort involved in running clinical patient studies is immense. Roche or Novartis can only start a clinical study once they’ve recruited 3,000 patients. Each day that goes by until they reach the 3,000 mark is a day less of patent protection. For a drug with an annual turnover of about 3.5 billion dollars, that costs the company about 10 million per day. Do you see what I mean? In future, Roche or Novartis will come to a platform like Midata and say: we need data from 3,000 healthy and ill people for a clinical study on a new type of Alzheimer’s medication. We then provide this data but only from account holders who previously agreed to let their data be used in this way. Part of the costs saved then go back into the cooperative.

**It remains to be seen whether this money doesn’t just end up back with the shareholders. In concrete terms, what do I get when I provide you with all my data? Apart from the warm and fuzzy feeling that I’m doing my bit for research. Can you give me a personalised eating plan, for instance, or help me lose my belly fat?**

As yet, that’s not possible because we don’t have enough data. But the goal is indeed to improve studies in future with the help of your data. In terms of diet, we already know that the genome doesn’t play a crucial role. It’s actually the microbiome or rather the gut bacteria. This is what dictates whether you get fat from eating white or brown bread. It depends on the individual make-up of intestinal flora. And that’s how companies and data service providers will spring up in future that can create effective diet plans based on your data.

**For free?**

Midata offers the platform and ensures that your data isn’t resold. We connect you and your data with different service providers. You then pay for the services from these third-party suppliers, just like you pay for Apple Music or Netflix. And that’s how a new services market is born. However, we keep the data secured and you have control over your account. You can delete your data or switch to a different platform whenever you want.

**What about data protection?**

You agree on what happens with your data. For example, you can store your data at Midata without anything happening to it. It’s a kind of PO box if you want to go back to the bank comparison. No one but you has access. And you can decide to only allow the data on your eating habits to be available purely for specific studies on diet. Or perhaps only for clinical studies for a new cancer drug. Either way, you decide who you let use which bits of data. What it comes down to is democratic, people-centred management of data.

**As opposed to the model used in the US and China.**

Exactly. We’re talking about market-driven surveillance capitalism in the US, as Harvard sociologist Shoshana Zuboff describes in her new book and the state-controlled model in China. Both of them are surveillance models. In Europe, and in Switzerland in particular, there’s a third option of not being under the control of shareholders or the state and instead have a people-controlled model. The value added goes back to the people. (I can see Ernst’s eyes light up.)

**Doesn’t that mean I’d always have to think about who I’m giving my data to and which data specifically? I’ve got enough to deal with in trying to find the cheapest health insurance and best mobile subscription each year. And then there’s the question of whether I should watch my favourite series on Netflix, Sky or HBO. Aren’t we already overwhelmed with decision-making?**

(Laughs) In the Middle Ages the prince used the same argument to avoid paying his employees. He gave them food, clothing and a roof over their head. Giving them a bank account and salary would have been too much for them to handle. When actually, it’s about self-determination. And yes, it is more tiring than heteronomy.

But this is all still a long way off. You still can’t analyse your own genome in Switzerland without authorisation from a doctor. Obviously you can still send a test tube spit sample of your DNA off to the US where various companies will decode your genome for a few dollars. You do have the option to do business that way. In which case, you get an analysis of your genetic origin and information about where your ancestors come from included in the price. In the US, about 30 million people have already done this test. It has let people find relatives they didn’t know they had and it’s even uncovered a serial killer.

Data protection and questions about ethics, such as managing public exposure, are just a few of the many challenges to come. But this technique also provides great opportunities. Just as everyone spends and invests money to contribute to an economic boom, digital self-determination could be the key to a fairer and more driven civil society.

Click [here]((https://www.galaxus.ch/en/User/patrick-bardelli-2732698) to follow me and stay up-to-date.

From radio journalist to product tester and storyteller, jogger to gravel bike novice and fitness enthusiast with barbells and dumbbells. I'm excited to see where the journey'll take me next.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all