Background information

Double the size for slow-paced pleasure

by Pia Seidel

From beer bottles to perfume bottles to jam jars – Switzerland recycles more than 90 per cent of its glass packaging. Broken wine glasses, on the other hand, have to go into the regular household rubbish. So far, pretty incomprehensible for a layperson. So why the distinction? The reason is lead – and money.

It’s a sunny Tuesday afternoon in autumn and I’m off to do some shopping. On my way to the grocery store, I make a stop at the glass recycling point. Along with wine, beer and juice bottles, I’ve got the shards of a broken drinking glass with me. Because the glass is transparent, it goes into the opening marked «clear glass».

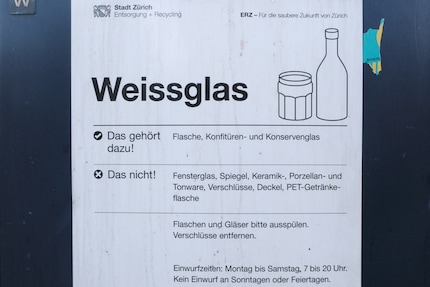

Or so I thought. At least until Vetroswiss, which is responsible for charging the prepaid disposal fee (VEG) and providing information about glass recycling, launched a poster campaign. This poster appeared right by my place.

Soon, black graffiti appeared above the cup: «Yeah, of course, this is porcelain» and above the broken glass: «Eh? Glass doesn’t go in the glass disposal?» My thoughts exactly. So, it’s wrong to throw broken glass into the glass disposal instead of the household rubbish.

But why?

The first thing I do is ask Vetroswiss. «Different types of glass have different melting points and chemical compositions. Drinking glasses, for example, contain higher amounts of lead, which, due to health reasons, is tightly restricted by law in food and drink packaging. This is the reason why drinking glasses have to be disposed of alongside household or construction waste,» explains Lukas Schenk. Markus Marchhart, Marketing Manager at Austrian food packaging distributor Müller Glas adds, «The varying composition would influence the quality in the melting tank.»

You’re maybe wondering now whether the lead contained in drinking glasses can also be harmful to your health. The answer is no – not unless you’re planning to store wine in them for months on end. Because this heavy metal isn’t very soluble, normal drinking doesn’t pose an issue. On the other hand, prolonged storage of acidic drinks such as wine can cause the lead to dissolve into the liquid (linked article in German). As a result, the chemical make up of their bottles is tightly regulated.

But not all drinking glasses are the same. Soda-lime glasses – the typical mass-produced glasses – don’t contain lead, meaning they can be thrown into the glass disposal. With lead crystal glasses, however, it’s a different story. The lead content in high-end wine glasses may guard them against breakage and make them sparkle and clink beautifully, but it also effectively bars them from the recycle bin. Unfortunately, this distinction isn’t clear to people like you and me, and so neither kind of glass can go in the recycle bin.

So now I understand why glass containers and drinkware can’t be flung together in the disposal. But why don’t we just have a separate bin for old drinking glasses? According to the Federal Law on Environmental Protection, «The generation of waste should be avoided as far as possible.» It immediately goes on to say, «Waste must be salvaged as far as possible.»

Phillip Suter, Chief Executive of Vetroswiss explains why this hasn’t (yet) been possible. «Alongside the known raw materials, manufacturers keep the formulation of their glass containers a closely guarded secret.» As mentioned before, the differing compositions of waste glass influence the quality of what goes into the furnace. In turn, this would affect Vetroswiss’s own glass formulation and therefore the quality of the recycled glasses. So that favourite glass you broke? It ends up in an incinerator via household waste.

But the glass also creates problems for incinerators. «Glass has a melting point of around 1,600 degrees Celcius, whereas incinerators work at a temperature of 700–1,000 degrees. Instead of becoming liquid, the glass clumps together and gets stuck in the tank. The remaining waste has to be landfilled, which is pointless and expensive,» says Suter.

So, where are bits of broken drinking glasses supposed to go? The glass is most likely to be recycled by the construction industry. «Theoretically, it’d be possible to use glass as a component of recycled concrete – only finely ground pieces, though. Larger particles, in the range of a few millimetres, would be corroded in the alkaline environment of the concrete (pH of 13) in what’s known as the alkali silica reaction. This would cause the glass to expand, which would eventually lead to cracks and chips,» says Dr. Frank Winnefeld, an expert in concrete and cement at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Testing and Research (Empa). But even when finely ground, there are obstacles to using glass. «The Ordinance on the Prevention and Disposal of Waste contains limits for contaminants, including lead, that must not be exceeded.» As a result, companies have limited themselves to recycled fragments of demolished masonry or concrete structures.

On the subject of drinkware, Marchart from Müller Glas has a second, more economical reason: «As an Austrian packaging company, we pay Allstoffrecycling Austria (ARA) a licence fee for every glass container sold. ARA uses the fees to organise disposal, recycling and collection points. Basically, this only applies to single-use packaging. There are no ARA fees for drinking glasses.»

Switzerland has these fees too, namely the prepaid disposal fee (VEG), levied by Vetroswiss. The VEG, too, only includes glass packaging with a volume of at least 90 millilitres – drinking glasses don’t fit the bill. At Vetroswiss, Suter won’t confirm Marchart’s assertion that drinkware isn’t recycled because nobody pays to do so. He says drinkware isn’t recycled because it may contain lead, which is why its disposal is financed by city charges (waste stamps, rubbish bag fees). It’s all done according to the polluter pays principle. If you generate waste, you should pay for its disposal.

What contradicts the polluter principle, however, is this: despite jam jars, pickle jars, and oil bottles being exempt from the prepaid disposal fee, they can still be thrown in the glass disposal and recycled. That means getting a lower VEG, and therefore a lower financial contribution to the cost of glass disposal.

So, in plain English: there isn’t yet a good solution for disposing or recycling drinking glasses. Packaging glass and drinkware can’t be thrown away together because of their differing lead contents. What's more, lead levels differ in every drinking glass and are kept under wraps by manufacturers. As a result, having a separate recycling container for drinkware wouldn’t work either. The glass could be ground down and made into recycled concrete for the construction industry, but the alkali silica reaction and caps on contaminant levels make the process complicated. On top of that, a relatively small amount of drinkware is disposed of, meaning that there’s little economic incentive to solve the issue.

Incidentally, Switzerland has been recycling glass since the mid-1970s. «Up to 90 per cent waste glass can be used in glass production, which leads to an energy saving of 25 per cent,» says Suter. During the oil price crisis, Swiss glass packaging manufacturer Vetropack began collecting waste glass to save money. A private transportation company wanted to establish a system whereby used glass would be collected directly from Swiss doorsteps. The scheme didn’t catch on. This was partly because the glass couldn’t be separated by colour, and only green glass could be produced from the resulting mixture. Partly, however, it was because people were afraid of being judged for their drinking habits. In 1976, this gave rise to the first publicly accessible recycling bins, so that wine and beer bottles could be separated by colour and disposed of anonymously.

Forty-five years later, on a sunny Tuesday afternoon, I did the same thing. It was the last time I made the mistake of throwing a broken drinking glass into the recycling.

My life in a nutshell? On a quest to broaden my horizon. I love discovering and learning new skills and I see a chance to experience something new in everything – be it travelling, reading, cooking, movies or DIY.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all