Background information

And cut! Horror on the Twilight set with Chuckesme, the killer doll

by Luca Fontana

Grand Moff Tarkin looks like a human in "Rogue One: A Star Wars Story". But somehow not. Tarkin is animated on a computer. Former ETH doctoral student Pascal Bérard did research for Disney and explains where the unease about digital humans comes from.

Computer-generated effects (CGI) solve problems that cannot be solved with real, practical effects. Most of the time. They still have one last hurdle to overcome: the depiction of photorealistic people.

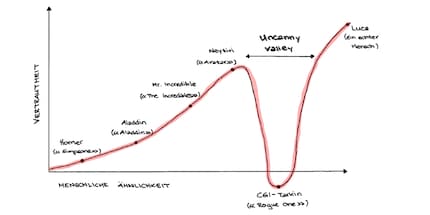

The hurdle has a name. Uncanny Valley. The term coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori stands for the unease we feel towards things that are similar to us, but still recognisably different. Robots. Dolls. Or computer-animated people in films.

"For programmers, the Uncanny Valley is the big enemy," says Pascal Bérard, a former doctoral student in computer graphics at ETH Zurich.

He works at Pascal Bérard.

He worked at Disney Research Lab in Zurich, one of two labs researching new animation technologies for films and series. Bérard and his team conducted research on the whole person, with a particular focus on the face. His work, however, focussed mainly on one organ: the eye. The aim was to make it more realistic, more authentic and less scary. To achieve this, Bérard worked on new capture technologies.

Bérard himself was involved in the creation of the character of Maz Kanata from "Star Wars: The Force Awakens", among other things. Bérard is not allowed to reveal exactly what articles he has contributed. But it's quite possible that it has to do with her eyes.

But why is it called "Uncanny Valley"? The origin lies in a graphic that relates familiarity and human likeness. The horizontal axis describes how much something resembles a person. The vertical axis, on the other hand, describes how familiar this something appears. The curve is ascending. Rising in the sense of "the more realistically animated, the more familiar the computer-animated figure appears".

Then the uncanny valley: a fall into the bottomless pit, just before the actual perfection.

For example, look at Homer from "The Simpsons"" or Mr. Incredible from "The Incredibles".

They are characters that represent people. Despite their obvious inauthenticity, they don't fall into the Uncanny Valley. Why? Because it is precisely this obviousness that prevents this from happening.

"If the character is simplified enough, our brain doesn't even think about the fact that the person shown is supposed to be a real person," says Bérard.

The more realistic the animation, the more the human mind tries to harmonise what is shown with reality. It wants to make the unreal real. A constant struggle. According to Bérard, this is not a problem as long as the battle is one-sided.

Because when Homer makes stupid jokes, we know he's a character in an animated series. Our brain adapts to that. However, when we watch "Rogue One: A Star Wars Story", things are different. There, real actors act with a character who only pretends to be real: Grand Moff Tarkin. The animation is too good not to be real. But it is not good enough to cover up the fact that it is not real. Our minds cannot resolve this conflict and reject the animation.

"A copy that is good but not perfect is repulsive," says Bérard, "the constant comparison with reality takes us out of the story. The copy achieves the exact opposite of what it should."

Sometimes computer effects are annoying. Thanks to ever-increasing computing power, Hollywood tends to use CGI more as an attraction than a tool.

However, effects companies such as ILM, Weta Digital and Digital Domain are masters of their craft. There isn't really anything they can't animate photorealistically. When Tom Cruise faces the tripods in Steven Spielberg's "War of the Worlds", you don't think for a second whether these alien vehicles are real or not.

Because you know that what is shown is not real. But the effects are good enough to prevent the conflict of wanting to make the unreal real from swelling. That's how your mind likes to be tricked. It willingly suspends its disbelief at the threat of an alien invasion in order to enjoy the film.

This is also called Suspension of Disbelief.

The mind is much more sophisticated when it comes to animating people.

"This is evolutionary," says Bérard, "because our minds have been trained for millions of years to read and interpret human faces."

When the first humans met in prehistoric times, there was no language to communicate. The human organ of speech was not developed enough. Let alone the mind. However, perception had learnt to distinguish the finest nuances and changes in facial expressions and to extract them into needs and intentions. So if the human face does not behave exactly as the mind is used to, the illusion falls apart.

But the face itself is not the most difficult part.

"It's the eyes," says the former Disney scientist. We make eye contact from birth. Especially when we talk to someone. That's why our mind knows the eye inside out. Bérard: "It's the first thing you notice about a computer-animated character if it's not perfectly animated."

The Uncanny Valley can only be avoided if everything is right. Facial expressions. Facial muscles. Skin textures. Even the wrong glow on the forehead can be irritating.

Or the geometry of the face shape from different angles.

Every digital artist - the people who programme the computer effects - interprets reality differently. This flows into the animation. A digital artist always has a theory that they put into practice. If the result doesn't look good enough, he goes back to the books.

"Finding out exactly what's wrong is difficult," says Bérard.

Sometimes it is the light that penetrates the skin and is reflected incorrectly by the various virtual skin layers. Prime example of this: Anthony Hopkins in "Beowulf".

Sometimes the lack of slight fuzz that we all have, which makes the skin look so rubbery. See "Polar Express".

Or incorrectly reacting facial muscles around the corners of the mouth and eyebrows. In

"A Christmas Carol" good to see.

With so many parameters, finding a needle in a haystack can take time. But deadlines for trailers and premieres have to be met. Then there's the budget: the longer it takes to programme a scene, the more it costs. Time becomes a critical resource. Effects end up in the film unfinished.

How can this be avoided? According to Pascal Bérard, the industry usually works with motion capturing and reference images.

First, movements and rough facial features are transferred to a computer model using markings on the body and points on the face. Maz Kanata from "Star Wars: The Force Awakens" was actually actress Lupita Nyong'o with dots and a camera on her face.

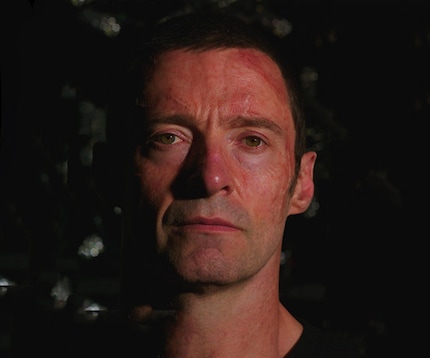

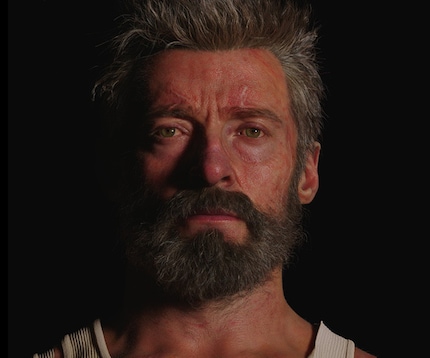

Then photos are taken in similar light and from different perspectives. Often on the film set itself. This allows programmers to compare their computer models with reality. For example, Hugh Jackman on the "Logan" set.

If the end result looks like Andy Serkis and the "Planet of the Apes" trilogy, nobody talks about the Uncanny Valley. Instead, there are Oscar nominations.

Actors who have already passed away are more difficult to digitise. Peter Cushing, who played Grand Moff Tarkin in "Star Wars" in 1977, has not been alive for 24 years. A double with similar facial features - Guy Henry - took over the acting. The same technique led to the uncanny Leia Organa in the same film. There played by the Norwegian Ingvild Deila.

The result looks good, but also kind of creepy.

"Obviously no reference photos with Cushing in similar light could be taken," says Bérard. This represented an additional hurdle in the animation of Grand Moff Tarkin.

The problem: programmers can see that "something" is wrong. But without a reference photo in which reality and replica can be compared 1:1, it is difficult to say "what" is wrong.

Pascal Bérard is certain: "In the future, it will be possible to overcome the Uncanny Valley. It's already possible to some extent". He alludes to examples such as Thanos in "Avengers: Infinity War" or Caesar in "War of the Planet of the Apes".

How computer-animated material is used is crucial. In large long shots, where the focus is not on the animation but on the set design, it is much easier to trick the brain and perception. "As soon as viewers have the opportunity to look at a computer-animated face longer and more closely, they notice the trick much more quickly," says Bérard.

One thing is clear: the Uncanny Valley is a beast that still needs to be tamed. But judging by the progress that has been made in recent years, it is not an impossibility.

In the 2013 film "The Congress", we see how Hollywood imagines it: The fictional studio Miramount wants to buy the character and film star image of actress Robin Wright and scan it to create a digital star. The contract is valid for 20 years. Wright will remain forever young in her films. In return, she is never allowed to set foot on a stage or film set again until the contract has expired.

I write about technology as if it were cinema, and about films as if they were real life. Between bits and blockbusters, I’m after stories that move people, not just generate clicks. And yes – sometimes I listen to film scores louder than I probably should.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all